Accra’s peri-urban space is a paradox of progress and neglect. That is, a zone of rapid urban transformation alongside infrastructural neglect. Amid dusty roads, burning refuse, scattered and uncompleted housing projects, vacant plots and tenure insecurity, state presence appears distant, if not altogether absent. Yet, beneath this visible disorder lies an intricate system of self-governance shaping the daily rhythms of peri-urban community life, including drain construction, land conflict mediation, and neighbourhood patrols. At the centre of these activities are Residents’ Associations (RAs), defined as locally organised collectives (made up of houseowners and tenants) that coordinate and facilitate everyday infrastructure and service provision where state authority is limited (Mapuva, 2011; Echessa, 2010). Acting as de facto gatekeepers of the urban fringe, RAs reveal how governance is negotiated and enacted, offering important insight into evolving forms of urban governance in peri-urban contexts in African cities.

A peri-urban community in Accra showing an untarred road and housing structures at different levels of completion. Photo by Divine Asafo (2018)

Drawing on insights from a stakeholder workshop and fieldtrip in Accra, and held in March 2025, this essay foregrounds the often-overlooked contributions of RAs in peri-urban Accra, Ghana. Considerably, we reimagine RAs in peri-urban Accra and by extension African cities as more than a temporary solution to peri-urban governance. Instead, they constitute the everyday actors that engage in community-driven practices of peri-urban transformation. The workshop was organised by the University of Hull in the United Kingdom and the University of Ghana, with support from the Ga East Municipal Assembly in Greater Accra region and attended by leaders from twenty-nine RAs in the Ga East municipal area.

Life on the urban fringe

Accra’s peri-urban areas are where the contradictions of urbanisation are most visible. These transitional zones, located between urban and rural areas and defined as neither fully urban nor rural, are shaped by overlapping land authorities, fragmented and uneven infrastructures, coupled with complex social relations (Meth et al., 2021; Ashiangbor et al., 2019). Amid the rapid urban sprawl outpacing the capacity of planning institutions, newly developed areas lack basic services such as piped water, tarred roads and proper sanitation. Here, the boundary between formal and informal is blurred and evidenced by houses built haphazardly and ahead of planning permissions, improvised service provisions, multiple sales of land, and increasing land tenure insecurities (Ashaigbor et al., 2019; Adusei, 2024; Amankwaa & Gough, 2021; Bartels et al., 2018).

These struggles are not unique to Accra. Across many African cities, peri-urbanisation exposes the limitations of formal governance and the endurance of improvisation (Meth et al., 2021; Bartels et al., 2018). Yet, in Accra’s case, the speed, magnitude and intensity of urban sprawl have intensified infrastructural fragility, with residents often describing their neighbourhood as partially developed and where State promises of development remain deferred. Consequently, community organisation such as RAs in peri-urban Accra has become a critical necessity rather than a choice. They foster community cohesion and coordinate local service and infrastructure provision. Beyond functioning as neighbourhood groups, they operate as adaptive governance structures that mediate between the state and the community.

From informal solidarity to organised governance

The emergence of RAs in peri-urban Accra is largely rooted in necessity, uncertainties and conflicts. In many newly developed yet poorly serviced peri-urban communities, RAs have evolved from informal networks (mostly via WhatsApp groups) of mutual support into organised groups that confront everyday challenges, including poor sanitation, haphazard development, inaccessible roads, insecurity and lack of potable water. Their emergence in serviced gated communities arises not only to promote community cohesion and strengthen collective welfare but also to enhance security within and around the neighbourhood. The majority of RAs, however, emerged as a response to tenure insecurity, particularly landguardism, a term used to describe illegal land protection arrangements where young people employ covert and often intimidating tactics (Adusei, 2024; Ehwi and Mawuli, 2021; Asafo, 2020). Many RA leaders described how their association was born after multiple land sales and boundary disputes resulted in intense violence and housing insecurity. As one participant revealed at the workshop: “we realised that if we acted individually over ownership of land, we would lose everything. Coming together gave us a voice.”

A defining feature of RAs in peri-urban Accra is the swift transition from informal solidarity to an organised governance system. During the workshop, it was revealed that a few RAs had constitutions, bank accounts, and were formally registered with the Registrar General’s Department in Accra to strengthen their organisational status. These steps were often accompanied by the creation of leadership hierarchies including chairpersons, secretaries and treasurers, mirroring state bureaucratic arrangements. For some RAs, this move towards formalisation was a way of asserting legitimacy, while for others, it was a strategic step to increase visibility and formally negotiate with municipal officials and utility providers. This shift from informal solidarity to structured governance mirrors a wider pattern across many African cities and urban peripheries, where collective organisation steps in to fill gaps created by a delayed or limited state presence (Gough & Yankson, 2006; Bartels et al., 2018). The outcome of this phenomenon, therefore, is not just a mosaic of hybrid institutions that step into the role of formal urban authority but also a contested space in which new actors such as RAs advance and negotiate their interests (Cobinnah & Darkwa, 2017).

Building from below: infrastructures of necessity

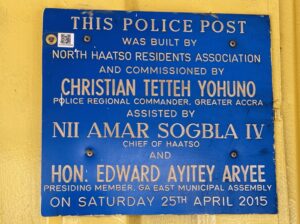

During the field visits in Ga East, the material imprint of RA activities was evident across several neighbourhoods. This can be grouped into three broad domains: service provision, security, and mediation. In terms of service provision, many RAs had collectively constructed culverts and police posts, installed streetlights and street signages, and facilitated access to potable water and electricity for households who lack access (see Figure 1). Beyond these contributions to physical infrastructure, RAs in peri-urban Accra also act as crucial social organisers, coordinating community neighbourhood security arrangements, often referred to as community watchdogs. The watchdog patrols the communities, particularly at night, to reduce criminal activities and ensure safety. In areas affected by encroachments, land conflicts and landguardism, RAs have instituted local dispute resolution mechanisms and serve as trusted intermediaries between residents, landowners, municipal authorities and security agencies, helping to broker peace and ensure community stability.

These multifaceted initiatives, though modest, carry symbolic weight in peri-urban development and governance processes. Together, they underscore the role of RAs as proactive agents of transformation operating at the intersection of state and society (Mapuva, 2011; Echessa, 2010). Their engagement do not only promote stability but also foster collaborative relationships with municipal authorities and service providers, encouraging orderly spatial development and mediating access to social services. While they are not officially part of the municipal system, their authority is locally binding and socially recognised. Notably, some RAs have successfully negotiated for municipal zoning plans and mediated the construction of roads, culverts, and access to water and electricity, helping to mitigate residents’ engagement with unregulated developments and enhancing their access to social amenities.

Culvert built by one of the RAs |  Street Signage erected by South East Haatso RA |

A Police post built by North Haatso RA |  A Police post built by North Haatso RA |

A rental hall built by North Haatso Residents Association |  A rental hall built by North Haatso Residents Association |

Photos taken by Divine Asafo, March 2025.

Financing these initiatives relies on a mix of membership dues, levies, voluntary labour, and the benevolence of community members. In one community, for example, each household contributes to an annual levy specifically allocated for road maintenance and street lighting. A few RAs have also adopted more innovative and entrepreneurial strategies for resource mobilisation for community development. A case in point is an RA that constructed a community hall, which it now rents out for social and religious events to generate revenue for ongoing interventions. This is reinforced by the growing diversity of residents whose varied expertise in areas of engineering, politics, leadership, business, security etc has become a strategic resource, enabling RAs to mobilise technical knowledge, engage state officials, and negotiate with utility providers.

Nonetheless, these collective efforts also reveal deep inequalities. Wealthier residents, often professionals and returnees from abroad, dominate leadership roles and contribute more financially, thereby shaping priorities in ways that marginalise tenants and lower-income households. As such, the collective spirit that underpin RAs is therefore intertwined with classed and gendered hierarchies of urban citizenship. Nevertheless, the resilience of these associations rest on their ability to navigate differences, drawing on diverse social networks and expertise to achieve common goals.

Negotiating the state: between autonomy and recognition

As argued above, RAs in peri-urban Accra operate at the margins of state visibility. Both collaboration and caution characterise their relationship with municipal authorities. On the one hand, RAs are indispensable intermediaries: they relay residents’ concerns, facilitate communication during development projects, and provide data on local demographics. On the other hand, their very existence underscores the limitations of the state, revealing how communities have filled governance vacuums through self-organisation and initiatives (Mapuva, 2011; Echessa, 2010).

The workshop revealed that municipal officials often welcome RAs’ contributions but remain reluctant to grant them formal authority. This ambivalence reflects a broader anxiety about non-state governance which is evident in most African cities (Lindell, 2008). Nonetheless, some RAs have begun to formalise their engagement by signing memoranda of understanding with local assemblies and utility providers, effectively becoming co-governors of their neighbourhoods. Others, however, are cautious about full incorporation, fearing that recognition might erode the flexibility and trust that sustain their operations. This tension between autonomy and formalisation is central to understanding the politics of peri-urban governance. It reveals how residents navigate the dual imperative of seeking legitimacy and preserving agency (Simone, 2001).

The visibility and recognition negotiated by RAs in peri-urban Accra extends beyond governance. It asserts residents’ right to belong. For RAs, such visibility is expressed both through infrastructure and formal recognition. The installation of street signages and streetlights, alongside the acquisition of registration and organised leadership, signals entry into the city’s symbolic and administrative order. In this way, the RAs leverage these tools to assert collective identity and challenge the marginalisation often imposed on peri-urban communities (Fält, 2016). Nonetheless, achieving visibility brings challenges, particularly in the form of regulatory scrutiny that many RAs perceive as excessive. Workshop discussions revealed that improved and organised neighbourhoods are increasingly subject to property taxes. While these taxes are not wholly objectionable, limited state involvement, inaccurate assessments, and lack of consultation have fueled non-compliance by members of RAs. As an adaptive strategy, they navigate this tension by alternating collaboration with state actors to safeguard community interests. This ambivalent politics mirrors the broader urban condition of Accra and by extension most African cities, where a limited state presence results in a selective response to municipal regulations (Cobinnah & Darkwa, 2017; Simone, 2001).

Rethinking governance from the periphery

Residents’ Associations are often portrayed as temporary responses to gaps in urban governance (Echessa, 2013; Lindell, 2008). Yet their significance extends far beyond service delivery. They embody a reconfiguration of how power, responsibility, and legitimacy is negotiated in contemporary African cities (Lindell, 2008). Their actions challenge conventional binaries such as formal/informal, state/non-state, and urban/rural, revealing governance as a plural, negotiated, and deeply social process (Goodfellow and Lindemann, 2013; Obeng Odoom, 2016).

In Accra’s peripheries, the everyday governance performed by RAs has produced a distinct form of neighbourhood urbanism, one that is not anchored in master plans or statutory frameworks but in shared labour, volunteerism, improvisation, and moral commitment to place (Amankwaa & Gough., 2021; Paller, 2021; Meth et al., 2021; Cobinnah & Darkwa, 2017; Ablo, 2022). These practices of collective self-provisioning illustrate how urban citizenship is being redefined through acts of participation rather than entitlement. Recognising this does not mean idealizing community resilience. Rather, we argue that RAs operate within a landscape of scarcity, uncertainty, and infrastructure neglect. Their success often depends on personal sacrifice and the quest for a peaceful life. As such, their persistence compels us to rethink what governance looks like when state presence is limited or delayed. Perhaps the lesson from Accra’s peri-urban is not that the state is absent, but that it has been quietly reconstituted through community actors who govern without official mandate, yet with impactful influence.

We conclude that as urban expansion continues, RAs will remain crucial entities for understanding how non-state actors in African cities navigate growth, conflict, and survival. They remind us that governance is not merely what the state does, but what different actors, particularly urbanites, make possible (Mapuva, 2011; Smith, 2018; Amankwaa and Gough, 2021). The city, after all, is not built only in concrete and policy, but in the invisible infrastructures of negotiation and shared responsibility that sustain life at its margins (Guma et al., 2023).

Divine M Asafo, is a Lecturer in Human Geography at the University of Hull. His research focuses on peri-urban development and change in African cities, with particular interest in the politics and governance of peri-urban land, everyday experiences of self-built housing, informality, and disaster risks and vulnerabilities. He has recently published on landguardism, fragile and compromised housing and peri-urban land market in Accra, Ghana.

Austin Dziwornu Ablo, is an Associate Professor of Geography and Urban Geographer at the University of Ghana with research interests in urban development, governance, environmental change, and socio-spatial inequalities in African cities. His work draws on critical social theory and political ecology, with particular attention to flooding, infrastructure, natural resource governance, energy transitions, housing, and everyday urban livelihoods in Ghana. He has contributed to research and writing on urbanization and land and resource governance.

Godwin Odikro, holds a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Geography and Resource Development from the University of Ghana. His research interests cut across Urban Geography, Climate change and Mobility, urban informality and Tourism.

Pln. Abubakar Mohammed-Mubeen, is a Senior Urban Planner at the Ga East Municipality in the Greater Accra Region and a member of the Ghana Institute of Planning (GIP) – Chair Person of the Greater Accra Zone. His interest areas are Local Governance, Development Planning and Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E). He is currently the Coordinator and Resident Researcher of a Research Study by Havard University and BlueDot Research Ghana on Property Rate Governance.