The US South has largely been perceived as a distinctive region bound to its racist past. Racism is certainly deeply entrenched in its culture and institutions, continuing to exert enormous influence over social and political behavior. Trump’s central message of xenophobia and racial antagonism resonated strongly with many residents of the region. Most Southern states supported Trump by wide margins. In the state of Louisiana, the Republican candidate defeated his rival by 20%. The recent election and ongoing debates about the Confederate regime seem to exacerbate the image of a region stubbornly holding on to white supremacy. For many outsiders, the region is seen as a deep and endless sea of bigotry, with opportunistic Republicans nurturing and working entrenched fears and hate simply to win another election.

Participants of the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965 (photo by Peter Pettus, Library of Congress, CC-BY)

There is some truth to this characterization, but it is also an oversimplification. The South is a new destination for immigrants from around the world. This has contributed to rapid demographic changes in metropolitan areas from Charleston, South Carolina to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. For instance, during the 2000s, the immigrant population in the United States grew by 24% and by 49% in 14 Southern and Midwestern states.[1] As geographers like Monica Varsanyi, Matthew Coleman, Patricia Ehrkamp, and others have shown, fast population growth in new destinations has spurred a backlash, with hundreds of municipalities and states devising innovative ways to render the lives of immigrants impossible.

While local and state-level forms of repression are well documented, we also know that there have been enormous levels of resistance in localities across the country. In certain instances, these battles have been supported by both African American activist organizations and progressive civil society. In other instances, white residents and their churches have lent support to the new immigrants in their area, motivated by feelings of empathy and concern for their fellow Christians. Thus, rather than new immigrants wilting under the pressures of white supremacy and the repressive state, many have connected to new allies, developed political capacities and friendships, and exerted their ‘right to have rights’ in their new homes. These small forms of resistance have flourished in some contexts and faded in others. In each instance, however, they introduce new cracks in racism’s cultural and institutional infrastructure, eroding its legitimacy and ability to reproduce itself over time.

These demographic shifts have combined with growing inequalities to give rise to new political coalitions seeking to break the stranglehold of neoliberalism and white supremacy. For instance, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, the mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, headed a campaign to make his city ‘the most radical city on the planet’.[2] Lumumba assembled a strongly progressive coalition and advocated for ways to finance cooperatives and public enterprises. In addition to pursuing his progressive policy once in office, he has also defended the city’s policy to not share immigration information with Homeland Security. He has demonstrated his commitment to a multiracial struggle for a more just and egalitarian city. The future of radical urban politics is arguably in Jackson and not Los Angeles or New York.

The South is therefore characterized by an entrenched white supremacy but also countless resistances and struggles that are taking it apart, street by street and town by town. The weakening of the old South would dramatically change the political landscape of the entire United States.

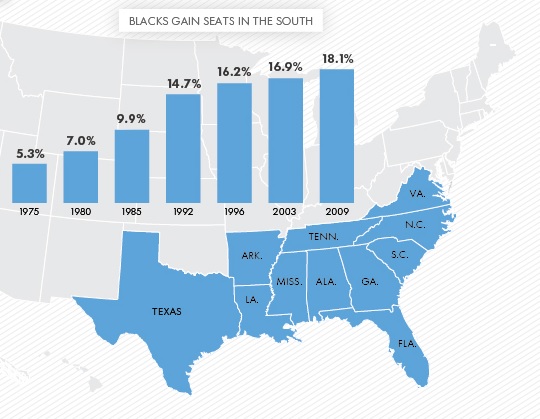

Blacks gain seats in the South (source: Frank Pompa, USA TODAY, 19 February 2013)

In spite of the changes unfolding in this region, the South has been overlooked by urban scholars. I performed a search for the 20 largest cities plus New Orleans in IJURR’s search engine (21 in total). In the 41 years of IJURR’s existence, there have been approximately 23 peer reviewed articles published on the region’s largest cities. This compares poorly to the dominant trifecta of US cities: New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. These three cities accounted for approximately 90 articles.

Table: IJURR articles by Cities

| 21 large US Southern cities | 23 |

| New York | 47 |

| Los Angeles | 25 |

| Chicago | 18 |

The first article published on the South (Richmond, Virginia) was in 1984. Two other articles were published in the 1980s, both by the same author (Joe Feagin) on the same city (Houston); and only one article was published in the 1990s (again Joe Feagin on Houston). For the first 23 years of the journal’s existence, there were four papers published by two authors on two of the most important cities in the South. Outside of Houston, much of the urban South was terra incognita. The 2000s and 2010s marked a change in the trend as more scholars started to focus on various cities throughout the region. The three most prominent cities to attract scholarly attention were Atlanta, New Orleans and Austin.

Documentation of public intervention and graffiti at Confederate monument sites in wake of Charlottesville riots (photo by Ryan Patterson, 14 August 2017, CC-BY)

Thus, metropolitan areas in the South are undergoing radical changes due to demographic transformations, severe inequalities, and flailing racist institutions. While there are general forces (globalization, state neoliberalism…) that are contributing to these changes, there are also regional and local structures that mediate how these general forces shape the everyday lives of inhabitants. In spite of this rich research terrain, most US scholars continue to flock to the saturated cases of New York, Los Angeles, and, to a lesser extent, Chicago. The enormous academic investments in over-studied issues (e.g. gentrification) in over-studied cities (e.g. New York) result in diminishing returns on knowledge and theory. Scholars flock to Brooklyn to say something marginally new about café life while disregarding the seismic changes unfolding in understudied Jackson, Mississippi and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. This regional myopia results in enormous levels of ignorance about these regions, forcing us to use ‘common sense’ stereotypes to explain phenomena unfolding within them.

Walter Nicholls

IJURR Board Member

April 2018

Selma then, Selma now: Victories in four key states (ACLU, 2016)

Footnotes

[1]Terrazas, Aaron (2011) “Immigrants in New-Destination States,” Migration Policy Institute, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/immigrants-new-destination-states, accessed March 15, 2018.

[2] Nichols, John (2017) ‘Jackson, Mississippi, Just Nominated Radical Activist Chokwe Antar Lumumba to Be the Next Mayor’, The Nation, https://www.thenation.com/article/jackson-mississippi-just-chose-radical-leftist-chokwe-antar-lumumba-to-be-the-next-mayor/, accessed March 15, 2018.

Houston

The Social Costs of Houston’s Growth: A Sunbelt Boomtown Reexamined

Joe Feagin (1985)

The Secondary Circuit of Capital: Office Construction in Houston, Texas

Joe Feagin (1987)

Are Planners Collective Capitalists? The Cases of Aberdeen and Houston

Joe Feagin (1990)

Atlanta

Going for Gold: Atlanta’s Bid for Fame

Drew Whitelegg (2000)

The Atlanta Experience Re-Examined: The link between Agenda and Regime Change

Clarence Stone (2001)

Charter Schools and Urban Regimes in Neoliberal Context: Making Workers and New Spaces in Metropolitan Atlanta

Katherine Hankins and Deborah Martin (2006)

Secessionist Automobility: Racism, Anti-Urbanism, and the Politics of Automobility in Atlanta, Georgia

Jason Henderson (2006)

Solidarity in Climate/Immigrant Justice Direct Action: Less from Movements in the US South

Sara Thomas Black, Richard Anthony Milligan, and Nik Heynen (2016)

Old Wine in Private Equity Bottles? The Resurgence of Contract-for-Deed Home Sales in US Urban Neighborhoods

Dan Immergluck (2018)

New Orleans

Tourism from Above and Below: Globalization, Localization and New Orleans’s Mardi Gras

Kevin Fox Gotham (2005)

Separate and Unequal: The Consumption of Public Education in Post-Katrina New Orleans

Joshua Akers (2012)

Racialization and Rescaling: Post-Katrina Rebuilding and the Louisiana Road Home Program

Kevin Fox Gotham (2014)

Austin

Inequality and Politics in the Creative City-Region: Questions of Livability and State Strategy

Eugene McCann (2007)

Contesting Sustainability: ‘SMART Growth’ and the Redevelopment of Austin’s Eastside

Eliot Tretter (2013)

Cultural Economy Planning in Creative Cities: Discourse and Practice

Carl Grodach (2013)

Individual Cases

Baltimore: Avoiding the ‘Soho Effect’ in Baltimore: Neighborhood Revitalization and Arts and Entertainment Districts

Meghan Ashlin Rich and William Tsitso (2016)

El Paso: North American Free Trade and Changes in the Nativity of the Garment Industry Workforce in the United States

David Spener and Randy Capps (2001)

Louisville: One Package at a Time: The Distributive World City

Cynthia Negrey, Jeffery Osgood, and Frank Goetzke (2011)

Miami: Back to Little Havana: Controlling Gentrification in the Heart of Cuban Miami

Marcos Feldman and Violaine Jolivet (2014)

Richmond: Industrial Transition in the Land of Chattel Slavery: Richmond, Virginia, 1820-60

Rodney Green (1984)

San Antonio: ‘You’re Good with your Hands, why don’t you Become an Auto Mechanic’: Neighborhood Context, Institutions and Career Development

Harald Bauder (2001)

St. Louis: Organizing the Ordinary City: How Labor Reform Strategies Travel to the US Heartland

Marc Doussar (2016)

Washington, D.C.: Permitting Protest: Parsing the Fine Geography of Dissent in America

Don Mitchell and Lynn Staeheli (2005)