Since 2020 it feels more important to note when and where you write your lines because current events move fast. Today is the 22nd of January 2021. I sit in my bedroom at my desk. I look outside my large windows at my neighbour’s doors, the pile of snow around the flats and the mountain tops around the village in the Austrian Alps. I am with my son and my partner. I am not in the city. I am not close to the university buildings of Vienna. The new infection numbers of COVID-19 have gone up again. Rather than loosened, the current lockdown will be prolonged with even more restrictive measures.

In these lines, I narratively trace processes of political discourse during the pandemic last year in Austria. It is also a personal reflection of navigating a dissertation and entering academia’s social field during a (global) critical juncture interwoven with the tale of a political economy. I do this from two spatial points: Vienna, where I study, work, and research. The other one is where I live with my family – a touristic village (3.462 residents) in the Tyrolean Alps. These two places are 500 km apart; they are also culturally, politically, and socially separate.

In the first year of the pandemic, starting my comparative research on territorial labour market policies has been suspended: conducting interviews, visiting sites, scientific exchange was all on hold – at least in the beginning. Then, communications adapted, my research topic became more precise. I began to reflect on the professional field I would enter, and my role in it as a global crisis unfolded for years to come bringing both despair and hope.

A spring like none before it

In January 2020, the first coalition of the conservative (ÖVP) and Green party (Greens) became the new Austrian government. The irregular election came after the conservative (ÖVP) and populist right (FPÖ) coalition dissolved in 2019 due to the Ibiza-Scandal. Some of the right-nationalist policies are still in place– the shift in policies and political discourse seemed irreversible.

Then, the pandemic became the top priority. In Tyrol, a mountainous and touristic region, the first virus spread was only taken seriously after bodged responses. For the first time, residents of my home village experienced the town spaces without any tourists. The lack of guests was noticeable everywhere. So used to tourists feeding them, ducks chased us during walks.

Ducks chasing. Source: Tatjana Boczy.

Not only wildlife is used to tourism; everything in this tiny town is oriented towards touristic exploitation. All spaces are dedicated to touristic flows. Businesses complained, but there was a sense of urgency and limited sacrifice. The government’s response was to invoke hope with new priority to welfare – “Whatever it takes”. The promise was to rollout sizable financial support in different areas. It was an hour to shine for the welfare system and social partnership after years of cutting back. At this time, criticism was not loud. The opposition backed the measures with only minor warnings of who not to forget. In those days, signs of spring brought a sense of hope overall. People made music for each other, clapped for health professionals and supermarket cashiers as “everyday heroes”. The first lockdown felt challenging but manageable in the public discourse.

At the university, PhD students almost welcomed a break from academia’s fast pace. Empirical work got postponed, conferences cancelled or postponed, and all teaching was (clumsily) conducted online. Sitting at my desk, I felt overwhelmed with news, information on virology and rising pressure to conduct pandemic research immediately. Unfocused, my attention wandered between project reports I had to write, new research pressures, and daily news.

Dissertation work found no place other than writing funding applications. Luckily, I wrote with three colleagues, and there were other PhD students to talk to. However, after rescheduling our interview three times, funding was denied. I tried to sort my thoughts on what to do after the rejection. Do I have the means, connections, and endurance for academia? Nevertheless, I found a precious nugget while application writing: Exchange with colleagues eased my typical PhD struggles. We set up a digital room to schedule writing retreats, exchange texts, suggest tools and methods, and talk about problems. It helped tremendously! We still meet regularly.

The summer of routines and hopes

In summer, measures were eased, and strange normality took hold. Protests began in the USA against police brutality that also sparked a discussion about race in Europe. In France, Belgium, the UK, and Germany, these discussions were more serious than in Austria. Here, the public discourse mostly revolved around race being a non-issue. Except for people already concerned with institutional racism, there was little awareness. The topic was swallowed by pandemic news, criticism of measures, first conspiracies spreading, and pictures of people not following restrictions. Fingers were pointed at young people and Balkan holidaymakers to bring the virus “by car”.

I began my routine of travelling between the university and family home again. Everyday research had changed but picked up its pace again. A novel sense of personal exchange accompanied academic interactions. People opened up about daily struggles, and a kind of solidarity took hold. Even in public spaces, people talked to other strangers about personal issues. It felt like a cultural eruption both in academia and on the anonymous urban streets.

New graffiti across a supermarket, Vienna 2020. Translation: Heroes do not work – they strike! Photo: Tatjana Boczy.

The Viennese tradition of nagging, however, did not stop. While Vienna is praised as the most liveable city, every Viennese will immediately complain about their urban surroundings. I vividly remember sitting on a new tram while an older woman loudly complained about a dirty piece of newspaper on the floor. The whole city is in shambles, she proclaimed. Where would all this [gesturing outside at businesses owned by migrants] lead, she asked. A sense of academic purpose took hold of me in those days: Listen. Discuss. Communicate truths.

I engaged more with those who worried, those who had heard half-truths and those who spread them. Understanding my privileged position, I felt the need to communicate insights, refer to research, facts, and lived experiences.

My dissertation got a final chance from me in those days. Two funding opportunities had opened. I wrote down my research plans as clearly as possible both to these funding bodies and myself. Sending these applications was rolling the dice one last time. If rejected, I would stop wanting to conduct my PhD research and pursue this insecure, precarious, and possibly toxic career.

Meanwhile, the political unity between government and opposition was starting to crack as Vienna’s city elections drew their first shadows. Faulty experiences of governmental support surfaced. Racist undertones took over the Vienna election and explanations of high infection numbers.

Autumn ghosts of old failures and first times

In autumn, suspense and waiting became harder. The world waited for a vaccine. I waited for funding decisions. Asylum seekers in Moria could not wait anymore. Individual Austrian mayors wanted to take in refugees from Greece: the mayor of Vienna and ÖVP party members in rural towns – spatial relations did not matter. To this day, these demands have not changed, nor have the NIMBY-solutions by the conservative-right within the ÖVP altered. Solidarity only for the few in his welfare regime. I became more confident that researching local welfare regimes was a relevant and current topic.

FPÖ election sujet, Vienna 2020. Translation top-down: Our home. The party of Viennese. SPÖ, ÖVP & Greens: Radical Islam. Photo: Tatjana Boczy

Reading the funding body’s decision on my application in October was a very physical sensation. Rather than crying, I screamed and ran towards a person I could hug. My PhD got funding for the next three years. Surprised and happy, I almost immediately worried about deserving it.

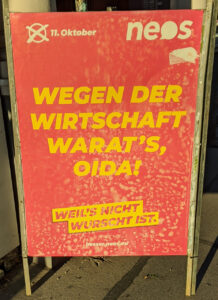

On the other hand, Vienna’s government elections in October brought no major surprises: The social democratic party (SPÖ) won. FPÖ lost many votes due to the scandal in 2019. Previously, the FPÖ had the mayor’s seat within their grasp. After the election of 2020, a new city coalition formed. Rather than continuing a Green–Social-Democratic rule, the SPÖ opted for a coalition with the market-liberal NEOS. At first, this move surprised. But then, it did not. Aside from personal quarrels, a more market-oriented approach was closer to the SPÖ’s policies than the eco-social transformation the Greens had in mind. A social-democratic and market-liberal coalition rules the city-state of Vienna now. Vienna took a new turn in its politics. The city government outlined economy-driven measures to revive growth.

NEOS election sujet, Vienna 2020. Translation (slang): It’s because of the economy, dude! Because it does matter. Photo: Tatjana Boczy

Autumn was also the time of the US election, riots, and undemocratic denials. A radical ghost haunted parts of the world. In Europe, as in Austria, criticism of pandemic measures grew as a second, more severe wave of infections began. Physical distancing measures were reintroduced with people demanding more exceptions as fatigue was noticeable. Through that fatigue, on the last day before another lockdown of restaurants, a mass shooting happened in Vienna’s party districts. There has not been a mass shooting in Vienna in four decades. A trauma swept over the city, and nobody could escape it. Blame was given to de-radicalization programmes releasing incarcerated individuals early.

Five days after the shooting, a protest car drove through Vienna’s streets, playing muezzin singing followed by gunfire sounds. Some Viennese were appalled, but the outcry vanished rather quickly. In the coming weeks, political Islam was demonized more than before with new policies to track down and close mosques deemed radical. For my research, this observation meant being aware of who is in or out of the group benefiting from social measures. Who are the ones under suspicion, and what do policies do to either combat or even increase inequality?

The winter’s road back to the (commodified) future?

November was the last time I spent in Vienna. Infection numbers did not go down. Increasingly, people I knew caught the virus. Simultaneously, vaccination became a reality. Discussions on measures and questions of liberal democracy became dominant. Opposition and activists criticized the lockdown, economic distress, and uncertainty ahead. Protests were again part of urban but also rural spaces.

Protest, Seefeld in Tyrol 2020. Translation: Peaceful Protest in every village, every city. No mandatory vaccination. Equality. We want to choose freely. On the 26th and 27th of December, everybody is invited to light a candle for his[sic!] freedom of speech. In front of every city hall and municipal office. Together we say NO. Photo: Tatjana Boczy.

A mixture of anger and fatigue accompanied the lockdown. Everything was closed again, with the strange exception of skiing lifts for resident’s recreation. My home village’s spaces looked almost like in every other winter season on sunny weekends: full of tourists. Day-trip tourists came here to get out of the urban environment.

Alongside the daily pandemic politics, the government also planned deep-cutting policies and structural changes. In December, a draft reform of university law was introduced. It continued the commodification of teaching and research rather than reversing the strange turns taken in the last two decades. Amid these suggested reforms, I wondered again if the university was a place I would like to work. I already experienced structural problems and conditions that opposed what I learned – and knew – was good research and teaching.

In January, I had planned to go back to Vienna. I could not. The government intensified lockdown measures as the more contagious virus variation B117 was detected in Austria.

Protests on the street of Vienna against pandemic measures erupted. People took to the street all over Europe against pandemic measures and slow or bodged roll-out of vaccinations. These anti-pandemic-measure activists are a mixture of anti-globalists, esoteric groups, xenophobes, right nationalists, and state rejectionists (Staatsverweigerer) bound together by various conspiracy narratives. Currently, some demonstrations start to become more violent.

Anti-Corona-Measures Demonstrations 16th January 2021, Vienna. Translation top-down: First banner: “Great exchange, Great Reset – Stop Globalist-Scum.” Second banner (partially obstructed): “Kurz has to go.” Photo: Ivan Radic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

My research was halted, rejected, reevaluated, and revived with a new purpose during this year. Witnessing the public discourses and political economy transformation both of urban and rural spaces, I feel like I have to become more equipped to argue false information and half-truths as part of my scholarly role. Even though the question of whether I can manage an academic career is still on my mind, it is postponed. I dream of becoming the kind of scholar that learns and inspires, that improves her rigorous research rather than her citation scores. Instead of pushing against other PhDs, I want to hook elbows with them in our endeavour to understand the social world. The dedicated funding for my PhD frees me to pursue more scientific integrity instead of system conformity, for now.

Tatjana Boczy (Twitter) is a sowi:doc fellow and PhD candidate in Sociology at the Vienna Doctoral School of Social Sciences, University of Vienna. Her PhD-thesis is about potential institutional changes in subnational welfare regimes in the UK and Austria and the consequences of spatial inequality.

All essays on Becoming an Urban Researcher During a Pandemic

Introduction: On Urban Field Research During a Pandemic

Liza Weinstein

Proximity and Distance: Navigating a Field of Tension in Urban Qualitative Research on the German Far Right During COVID-19

Gala Nettelbladt & Leon Rosa Reichle

Doing Fieldwork in Informal Settlements in Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area During the Pandemic

Francesca Ferlicca

What are Cities like when Affective Encounters Change?

Hang Wei

Hope in Action – Responding to the Pandemic as Researcher-Activists?

Taru

Credence, Chlorine and Curfew: Doing Ethnography Under the Pandemic

Sara Nikolić

More Haste, Less Speed: Experiences of Conducting Doctoral Research During a Pandemic

Alison Pulker

“Stay at Home”: Navigating Urban Research and Fieldwork During a Pandemic

Angana Banerjee

The Complex Production of Urban Research During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Safa H. Ashoub

The Hammer and the Dance of Urban Research During a Pandemic: Waves of Despair and Hope (A PhD’s diary)

Tatjana Boczy

Related IJURR articles on Becoming an Urban Researcher During a Pandemic

Rethinking Urban Epidemiology: Natures, Networks and Materialities

Meike Wolf

Comparative Urbanism: New Geographies and Cultures of Theorizing the Urban

Jennifer Robinson

The Urban, Politics and Subject Formation

Lisa M. Hoffman

Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?

Ananya Roy

The Urban Question as Cargo Cult: Opportunities for a New Urban Pedagogy

Rob Shields

The Comparative City: Knowledge, Learning, Urbanism

Colin McFarlane

© 2021 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.