The COVID-19 pandemic is a global phenomenon of high urban incidence, a multi-dimensional issue in light of its causes, viral spread, and consequences on health, economy, urban environment, epidemiology, etc. The virus outbreak and the further government preventive measures stressed the pre-existing inequalities in informal settlements around the world. Furthermore, as a consequence of overcrowded housing conditions, lacking access to water and sanitation systems, inhabitants of informal settlements have experienced harsh difficulties in implementing virus mitigation measures, such as handwashing and social distancing. In addition, preventive isolation policies impacted the inhabitants’ economic reliance on casual labour and micro-businesses, causing an unreplaced loss of income.

Civil society organizations in informal settlements played an active role in this critical context. They deployed reactions and strategies of self-organization and solidarity aimed at providing immediate and medium-term responses to the emergency. However, only a few academic publications have gone further than simply acknowledging the harsh social consequences of the pandemic. In particular, Franco et al. (2020) mapped the repertoire of collective action in Latin America “from civil society in/for informal settlements focused at a neighbourhood level on emergency measures around food security, pedagogies for prevention and self-care, sanitation and income relief” (524). This essay intends to broaden this insight by studying the Argentine experience.

This essay proposes, on the one hand, to reflect on the effects of the pandemic in the informal neighbourhoods of the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, highlighting the repertoire of collective actions implemented by civil society organizations to face the challenges posed by the pandemic. To this end, two case studies will be addressed: a set of three informal settlements (Costa Esperanza, Costa del Lago, and 8 de Mayo) in the Municipality of San Martín and land squatting (Guernica) in the Municipality of Presidente Perón. On the other hand, this essay aims to describe the challenges and strategies that were implemented to carry out fieldwork during the pandemic in the selected case studies. In the last section I evaluate these local bottom-up responses and present a set of considerations on the research strategies adopted in the fieldwork. Also, I will offer a further remark on doing fieldwork during the pandemic following protocols and preventive measures, emphasizing the importance of continuing fieldwork safely.

Doing fieldwork in three informal settlements in the Reconquista river basin during the pandemic

The scope of my doctoral research is to investigate the role that the State plays in the regularization and socio-urban integration of three informal settlements in the Reconquista river basin in Buenos Aires Metropolitan area, as well as the state-society interactions and their effects in shaping the materiality of the urban space.

The three selected settlements, Costa Esperanza, Costa del Lago, and 8 de Mayo, located in the Municipality of San Martín, are the result of organized collective land squatting of floodable areas which took place in the late 1990s. According to RENABAP, these settlements currently have a population of 9,490 people, approximately 2.3% of the total population of the Municipality of San Martín (414,196 inhabitants). These settlements have a deficient provision of infrastructure and urban services (pavement, sidewalks, drains, sewers, mains water, lighting). There are no schools, kindergartens, health centres, hospitals, or ATMs within these neighbourhoods.

In these three neighbourhoods, several problems were unleashed by the conditions of preventive isolation measures and by the pandemic itself: the discontinuity or loss of labour income of the households, the difficulty of accessing basic food and water services, and, finally, the overcrowding. In addition, the negative effects of the pandemic and isolation policies on children are deeply concerning. The suspension of face-to-face classes has deprived many of them of free school lunches and has led to massive school drop-out. Although households access the internet through Wi-Fi or mobile data, the quality of service is poor, which makes distance education almost impossible. In this regard, only a few homes have the availability of a computer or a cell phone. However, despite the complex situations faced by the population of these settlements, it is possible to observe some community strategies to face these challenges. For example, many civil society organizations implemented solidarity actions to ensure basic food provision to the most vulnerable communities. The two common modalities of food security were the delivery of food products to families (food baskets) and the support of communal kitchens (comedores populares or ollas populares).

Food provision by “Sueños felices” communal kitchen in Costa Esperanza informal settlement. Photo: Francesca Ferlicca.

Doing field research in an informal settlement requires connecting with local actors through the creation of networks. In the context of preventive isolation measures during the pandemic, it was hard to weave these connections, and the context forced me to identify alternative strategies to get in touch with local stakeholders. I implemented the following actions. My initial approach to the neighbourhoods was through a DETECTAR[1] device, jointly implemented by the Municipality of San Martín and the local grassroots movements in Costa Esperanza. My main goal was not to observe the detection of coronavirus cases but to strategically use the device as an entry point to visit the neighbourhood and to meet grassroots organization leaders. These leaders provided me with the contact details of other relevant local actors, such as inhabitants and community priests. Then I started a collaboration through periodic meetings via Zoom, sharing materials, interviews, and reports with a research group from a local university (UNSAM), “Migrantas en Reconquista” which had previously carried out research activities in the field. This collaboration ultimately allowed me to interview other local stakeholders.

Figure 2. Covid-19 testing operational plans (DETECTAR) implemented by the Municipality of San Martín in Costa Esperanza informal settlement. Photo: Francesca Ferlicca.

The pandemic context pushed me to find creative and safe strategies to continue fieldwork both virtually and in person. For my research, I have carried out face-to-face (following Covid-19 protocols) and virtual interviews via Zoom with four types of local actors: inhabitants, grassroots organization leaders (face-to-face interviews), municipal and provincial officials, and water management company officials (Zoom interviews). These interviews intended to investigate the different rationalities at play in the complex governance of the territory. Furthermore, I organized, along with a fellow architect who was investigating the same territory, a collective mapping workshop to reconstruct the spatial history of the neighbourhoods. We invited inhabitants of these three neighbourhoods, and we printed cartographic material to be able to collectively map the spatial experiences of the participants. In order to avoid the risk of infection, we performed this activity in an open space, keeping distance among the participants and using mandatory mask protection.

I also used cartographic tools and geographic data for mapping as well as visualizing and exploring geographic information. I reconstructed the evolution and expansion of the three informal settlements over time. Thanks to these cartographic methods I was able to visualize the urban structure, the presence of public spaces, and the lack of access to basic services.

An experience of action-research in a ‘land squatting’ in the outskirts of Buenos Aires Metropolitan area during the pandemic: the case of Guernica

Since July 2020, about 70 attempts of ‘land squattings’, known in the local context as tomas de tierras, have been registered in Argentina in the areas of Great Buenos Aires and La Plata, concentrated mainly in the outskirts of these metropolitan areas. These land takings, historically originated in the ’80s, are massive, collective, and organized land squattings that give rise to informal settlements known in Argentina as asentamientos.

These recent ‘land squattings’ are shaped as housing responses enacted by low-income sectors that struggle with situations of extreme labour and economic precariousness. The great majority of the families that occupied vacant land in Greater Buenos Aires and La Plata could not afford their rent anymore as a result of the government’s lockdown measures and the socio-economic crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic. Many others just “escaped” from overcrowding living conditions.

Although these unexpected land squatting outbreaks were not the original subject of my research plan, I decided to explore and include them because of both their scale and their capacity to illustrate the increase of housing shortage during the pandemic. I was especially interested in analysing the tomas de tierras phenomenon, i.e. the collective action process of land squatting that precedes the conformation of informal settlements.

In particular, I focused on the recent process of occupation of a peri-urban land in Guernica, a locality in the South of Greater Buenos Aires, and the informal development of a residential neighbourhood. Guernica is a remarkable example to understand the resilient co-production of an informal settlement, its inhabitants’ bottom-up organizational capacity, and their ability to elaborate alternative proposals beyond the action of the State.

From the very beginning, the inhabitants intended to create a neighbourhood respecting provincial regulations. They envisaged that in doing so the neighbourhood might have been regularized by the public authorities and eventually served with access to public services.

A precarious zinc sheet shelter in Guernica land squatting. Photo: Francesca Ferlicca.

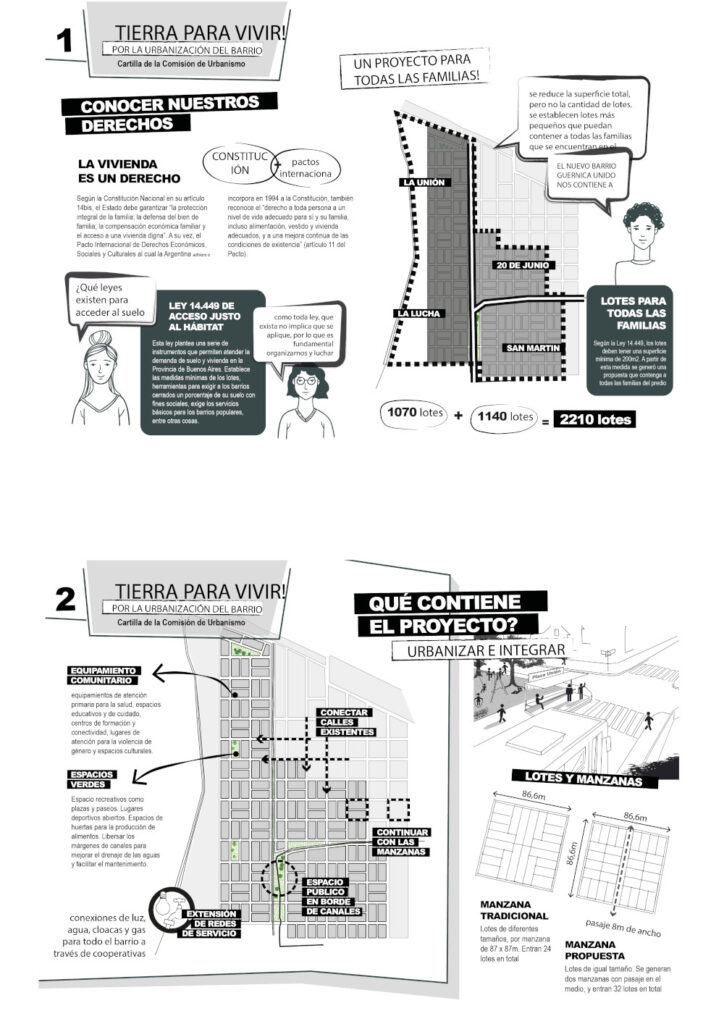

I participated in a first mapping on the neighbourhood design as set up by the inhabitants. I recognized a disorderly and discontinuous plot, the lack of green spaces and facilities, and the almost non-existent distances between plots and watercourses. Through a process of collective mapping and participatory design, I took part in the elaboration of a preliminary urban project. Then, facing a growing demand from the inhabitants of the toma, an Urban Planning Commission (“Comisión de Urbanismo de la Recuperación de Tierras de Guernica”) was created. The Commission was composed by students and academics of the Geography and Architecture departments of the University of Buenos Aires and the University of La Plata. The Commission, along with the assemblies of delegates and political organizations, elaborated a detailed urban project. The proposal was based on the Law of Fair Access to Habitat, No. 14.449 (Ley de Acceso Justo al Hábitat, N° 14.449) approved in November 2012, which provides a framework for addressing land and housing problems in the Province of Buenos Aires. The project, which initially functioned as a tool for the creation of a regular neighbourhood in compliance with provincial legislation, became afterwards a tool for political activism.

The Guernica land squatting masterplan elaborated by the Urban Planning Commision. Image: Comisión de Urbanismo de la Recuperación de Tierras de Guernica.

The Urban Planning Commission held online group meetings (twice a week over the course of three months) to advance in the elaboration of the urban project. During our field activities —all outdoors— (surveys, measurements, meetings with block referents, assemblies) we respected social distancing, wearing face masks and avoiding gatherings.

On 29 October 2020, Guernica land squatting was evicted by the provincial police despite the global “Zero Evictions for Coronavirus” campaign led by the International Alliance of Inhabitants. Two thousand five hundred families remained homeless, and the provincial government provided no substantial aid.

Conclusion

The collective strategies deployed by local civil society organizations in the three neighbourhoods of the Municipality of San Martín showed a high degree of collective organizational skills and territorial solidarity. These groups were partly able to mitigate the effects of the preventive isolation measures. Yet after the first three months their efforts resulted insufficient and unsustainable. In addition, the meagre financial support offered by the National State to the inhabitants was quickly discontinued: in April 2020, many of the informal and unemployed workers who reside in the area received an Emergency Family Income (Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia) of an approximate monthly amount of USD 115, however this benefit was withdrawn after only six months.

As shown in the Guernica case, the effects of the lockdown have worsened the existing structural housing crisis. Many families could not afford to pay rent anymore and were forced to resolve their housing situation by squatting vacant land in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area. National State initiatives were reduced to the criminalization and judicialization of the land occupation without offering concrete answers to the housing demand of the occupants (such as subsidies for tenants or provision of site and services). Furthermore, the Provincial State limited its actions to the execution of judicial decisions until the eviction took place. On the other hand, the case of Guernica shows bottom-up resilient organizational capacity, illustrated by an unprecedented collaboration among the low-income sectors, the University, and the social movements.

In my fieldwork experience, I adapted my research methodology holding online interviews, virtual collaborations with research teams from local universities, using cartography and audio-visual materials, performing participant observation and field visits. I also had the chance to observe Covid-19 testing operational plans in informal settlements and to visit communal kitchens (comedores populares or ollas populares). I built and strengthened academic networks and interacted with public officials, leaders of social movements, and community priests (curas villeros). In the end, all this gave me access to datasets and local key informants that in turn provided me with a revealing understanding of the territory.

Public officials’ statements should be informed by participant observation and fieldwork. This becomes even more urgent in the specific context of the pandemic, since social researchers can easily be persuaded to avoid doing fieldwork and making contact with the inhabitants of high-risk contagion areas. Without face-to-face interviews with key informants, neighbours, and social movement leaders, I would have never been able to assess the magnitude of the need for local housing. If we comply with protocols and preventive measures, we can safely develop our research in enlightening ways. We should not forget that, as scientists, we have an equal ethical commitment to our research and to public health.

[1] DETECTAR (Dispositivo Estratégico de Testeo para Coronavirus en Territorio Argentino) is a device created by the Ministry of Health of the Nation for the early detection of coronavirus cases. Initially, it was carried out in vulnerable neighborhoods in the City and Province of Buenos Aires, but it has already been carried out in other provinces as well.

Francesca Ferlicca (Twitter) is a PhD candidate in Regional Planning and Public Policy at the IUAV University of Venice. She is an urban planner who graduated in Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Roma Tre. Her research interest lies in housing policies for the informal city, especially in Argentina.

All essays on Becoming an Urban Researcher During a Pandemic

Introduction: On Urban Field Research During a Pandemic

Liza Weinstein

Proximity and Distance: Navigating a Field of Tension in Urban Qualitative Research on the German Far Right During COVID-19

Gala Nettelbladt & Leon Rosa Reichle

Doing Fieldwork in Informal Settlements in Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area During the Pandemic

Francesca Ferlicca

What are Cities like when Affective Encounters Change?

Hang Wei

Hope in Action – Responding to the Pandemic as Researcher-Activists?

Taru

Credence, Chlorine and Curfew: Doing Ethnography Under the Pandemic

Sara Nikolić

More Haste, Less Speed: Experiences of Conducting Doctoral Research During a Pandemic

Alison Pulker

“Stay at Home”: Navigating Urban Research and Fieldwork During a Pandemic

Angana Banerjee

The Complex Production of Urban Research During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Safa H. Ashoub

The Hammer and the Dance of Urban Research During a Pandemic: Waves of Despair and Hope (A PhD’s diary)

Tatjana Boczy

Related IJURR articles on Becoming an Urban Researcher During a Pandemic

Rethinking Urban Epidemiology: Natures, Networks and Materialities

Meike Wolf

Comparative Urbanism: New Geographies and Cultures of Theorizing the Urban

Jennifer Robinson

The Urban, Politics and Subject Formation

Lisa M. Hoffman

Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?

Ananya Roy

The Urban Question as Cargo Cult: Opportunities for a New Urban Pedagogy

Rob Shields

The Comparative City: Knowledge, Learning, Urbanism

Colin McFarlane

© 2021 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.