This is the first blog from Dr Ulises Moreno-Tabárez (Event Organiser) for the Afro-Indigenous Spectralities series. The blogs are linked to a series of events funded by the IJURR Foundation Majority Workshops project running from June-December 2025.

“This blog narrates the work leading up to our first in-person encounter, including the open call and selection process, the three-day virtual seminar, the formation of ten thematic teams, early project strands, and why we decided to move towards a strengthening in-person gathering in Acapulco. It also includes two short reflections from doctoral researchers in the network: one on the possibilities and limits of virtual collaboration, and another written from fieldwork in poetic prose.”

Introduction

When we launched the Afro-Indigenous Spectralities call, we imagined a space of encounter between researchers, artists and activists interested in thinking together about coastal urbanism, climate grief and the afterlives of ethnoracial capitalism. The response was remarkable: thirty-six people applied from different places and disciplines, some with established careers, others at earlier stages, but all sharing a common interest in the intersections between territory, ecology and memory.

From that group we selected thirty participants, including the organising team itself. From the outset, we were clear that we did not wish to maintain hierarchical distinctions between coordinators and participants. All of us were part of the same collective experiment. Yet, as with most of these coalitions, the space and time where our trajectories intersect vary, and the organising team continues to hold the work together.

A three-day inaugural seminar

Our first meeting took place online over the course of three days. It marked the formal beginning of the seminar and was also the first opportunity to see one another, even if only through screens. Dr Ulises Moreno-Tabárez opened with a lecture on spectrality as method, inspired by his ethnographic work on water rituals in the Costa Chica region. The talk did not aim to provide answers but to open a space for shared reflection (See Figure 1). Questions soon arose: What does it mean to work with spectres? How does that notion translate into our own disciplines? What place does absence occupy in research?

Figure 1: Screenshots of initial workshops to introduce the seminar series. There were about 40 people present, but the recording only shows those whose cameras were turned on. Screenshots by Ulises Moreno-Tabarez.

After this introduction we moved on to the logistical aspects. Each participant presented a brief outline of their current work, and on the basis of those thematic affinities we formed ten teams of three people. The combinations were as diverse as the themes themselves, ranging from extractive urbanism and agroecological knowledge to urban racialisation, disaster management and grassroots planning.

First traces of work

Some groups quickly found their own rhythm. They began to write, exchange ideas and design their outputs. From these early efforts emerged projects that already show a clear direction: a manual of virtual ethnography to support young researchers working with coastal communities to document their relationships with mangroves; an initiative on public health and urban livestock practices; debates around new environmental laws and constitutional reforms; stories and essays exploring urban grief after hurricanes; and a collective digital archive that is gradually taking shape as a regional platform for the network.

Not all groups advanced at the same pace. Some conversations faded due to lack of time or coordination, while others needed more support to consolidate. From the original thirty participants, twenty-two remain actively involved, a high number considering that in our experience, groups of this kind often dwindle to single digits. We have been deliberate about working in teams, even though collaboration is not everyone’s strength. Yet this is precisely the core of network-building: learning to work collectively, to share responsibility and to think together. There will always be time for individual work, but this network is not that space. We had placed our trust in autonomy as a principle, but soon realised that autonomy alone was not enough. The network needed a shared pulse, a moment to meet again and recognise one another.

Between presence and absence

In this section, two of our spectres, both doctoral researchers with distinct trajectories, share fragments of their experience within the Afro-Indigenous Spectralities network.

From Acapulco, Astrid Paola Chavelas López writes from the field. Her text, The Spirits that Inhabit the Stones, reads like a diary entry from her ongoing fieldwork on the coast, where she and her team are developing a self-managed research project as part of this seminar series. Her prose moves between ethnographic observation and poetic gesture, tracing how the landscape itself becomes an archive of spirit, loss and persistence.

Meanwhile, from Mexico City, Ivette Salinas Carranza reflects on the possibilities and limits of virtual collaboration, offering an intimate view of what it means to work collectively across screens, time zones and uneven access. Her words speak to the patience and care required to sustain a sense of presence when bodies remain dispersed.

Together, these two accounts bring us closer to the pulse of the network as it unfolds between distance and proximity, between what can be seen and what is still taking shape.

The Spirits that Inhabit the Stones – Astrid Paola Chavelas López – Acapulco

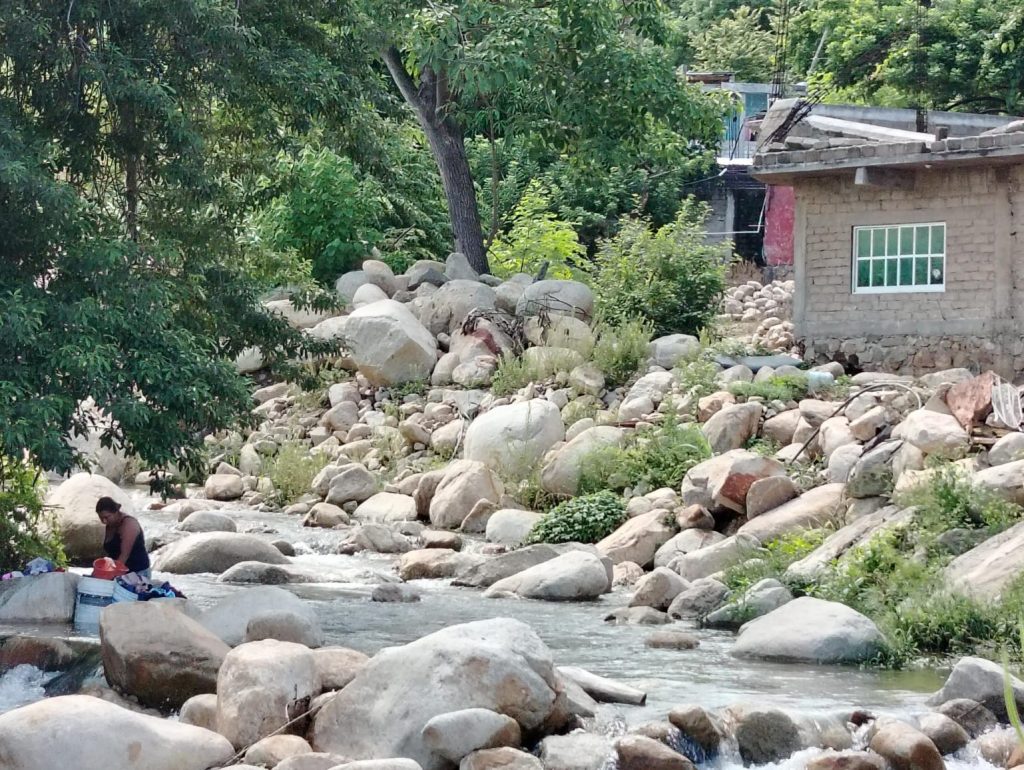

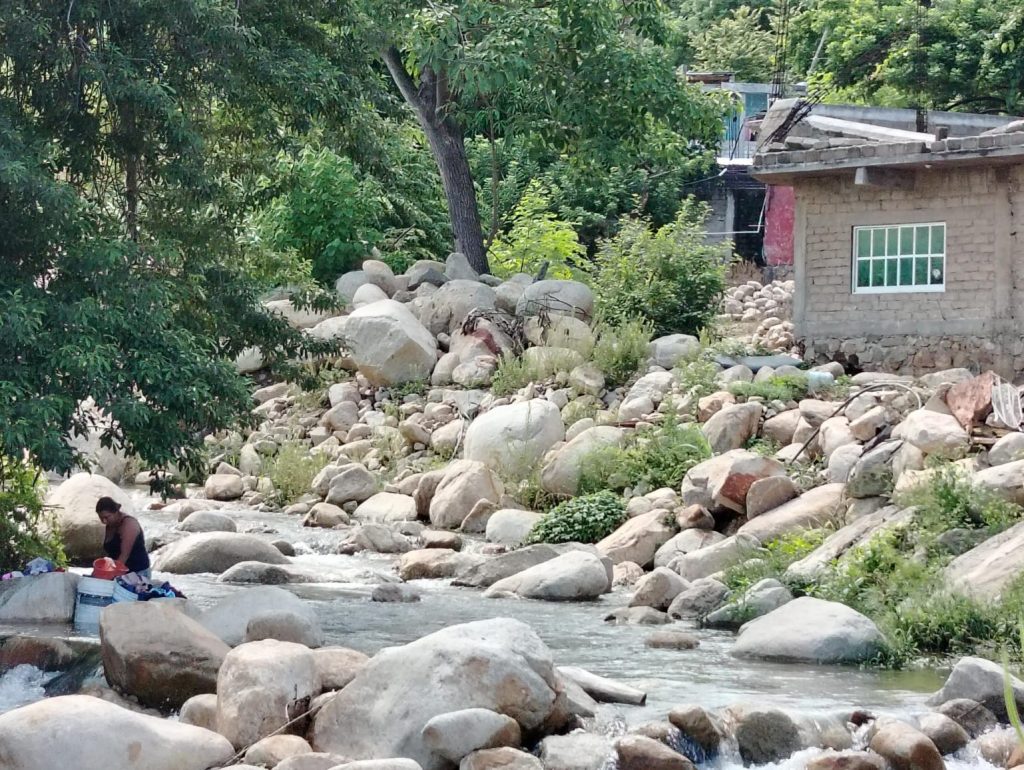

It is August, the end of the term. I returned to the port after crossing the marshland to the sea. Then another geography, another coast opens before the wonder of how dissent is built into the everyday, how the quiet of the afternoon dissolves into the weave of the hammock, how grief is stitched into space. In the distance, the voice of the stream sings its truth among the stones. Women seek shade under the tamarind tree as they lay out the clean clothes to dry; girls and boys play, jumping about, tadpoles who know themselves to be free and safe in their world. (See Figures 2 and 3)

Figure 2. A family enjoying the river, photo by Astrid Paola Chavelas López

Figure 3. Woman drying clothes on the rocks, photo by Astrid Paola Chavelas López.

The rain greens the coastal urban landscape. The heat wounds the ocean. In San Isidro, Tropical Storm Erick and the changing light disrupt the home production of mezcal by Doña Mayte. Summer drags the clouds; over the sea the fury of lightning gathers. The safe place becomes a boat, fragile, shipwrecked amid the river of stones.

The territory speaks. It pronounces the language of the spirits that inhabit it. On the streets, the damage remains. The social phenomenon extends beyond the heaps of rubble, tin and soil. A charred urban plain rests before the patience of the grass.

Figure 4. Abandoned van in the street, photo by Astrid Paola Chavelas López.

It is the season of watermelons. Piles of local fruit gather along the pavements. Conversation filters through the questions. The spirits. What was, what has been. What remains. Rodrigo’s birthday coincides with the date held in this personal calendar. His umbilical cord fell off the day a wind of three hundred kilometres per hour unleashed its fury on years of precarity. The rural health system is a complex metaphor.

Silence weaves the answers after the October that tore the reeds from the ground. The stream runs down the main street. Faith kneels before the storm. Hope is a child with wide eyes. An umbilical cord of water links him to his tona. When he grows up, he will be the voice of the stream. The stones keep the strength of the spirit that sustains his home.

Reflection – Ivette Salinas Carranza — Mexico City

Participating in the building of the Afro-Indigenous Spectralities network in virtual form has been both enriching and challenging. There are moments when technical issues, such as power cuts or unstable internet connections, interrupt our communication, but despite that, we have managed to keep the exchange and the collective work alive. From a distance, I have come to value collaboration as a form of extended presence, where each contribution, however small, becomes part of a shared fabric. Working in virtual spaces also means facing the limits of time and energy that do not always align. Yet there are moments of connection that remind me that a network is not built only through physical proximity, but through care, attention and listening. Technology has been an important tool that allows us to connect from different places and sustain this process. The diversity of people and backgrounds has also expanded our perspectives, enriching the collective work.

Throughout these months, relationships have formed that carry academic, political and affective weight. It is surprising how affinities emerge even without meeting in person, how we can articulate shared questions and experiences across distance. This process has shown me that collective work does not always require physical presence to feel real or transformative.

What I look forward to now is meeting in person, to speak and listen without screens, and to have conversations that are not constrained by time or connectivity. I hope this encounter helps to consolidate trust, clarify directions and open new possibilities for collaboration. The physical presence of others will, I believe, strengthen what we have already begun to build together.

Rethinking the format

These reflections led us to reconsider our structure. Originally, the plan was to have one in-person meeting at the beginning, then work virtually until the final gathering in December. But it became clear that, without sustained coordination and shared time, the network risked becoming fragmented.

So we decided to change course. Rather than expecting constant virtual engagement, we will now host an in-person event in Acapulco, a space for everyone to meet, reconnect and strengthen the regional network we are slowly building. It will also allow participants to experience the coastal landscapes that anchor our theoretical work: the very places where urbanisation, ecology and memory converge.

This gathering is not just logistical. It is methodological. We see it as a gesture of care, an opportunity to transform our dispersed conversations into a collective practice, to let the network breathe and grow.

As we move towards December, we know that the project’s success will not be measured only by outputs but by the relationships that endure. If the spectral has guided us so far, perhaps it is because this kind of collaboration, stretched between presence and absence, theory and territory, was always meant to appear, disappear and return in unexpected ways.

Next: Blog 2: Common Spectralities: Territorial Conjurings of Presence and Memory

Previous: Reimagining Urban Design Through the Pedestrian’s Lens

Back to Voices from the community (main blog page)

**************************************************************************************************

Comienzos espectrales: tejiendo la red afroindígena en Guerrero Cuando lanzamos laconvocatoria de Espectralidades Afroindígenas, imaginamos un espacio de encuentro entre investigadores, artistas y activistas interesados en pensar colectivamente el urbanismo costero, el duelo climático y las secuelas del capitalismo etnorracial. La respuesta fue notable: treinta y seis personas postularon desde distintos lugares y disciplinas, algunas con trayectorias consolidadas, otras en etapas más tempranas, pero todas compartiendo un interés común por los cruces entre territorio, ecología y memoria.

De ese grupo seleccionamos treinta participantes, incluyendo al propio equipo organizador. Desde el principio tuvimos claro que no queríamos mantener distinciones jerárquicas entre quienes coordinaban y quienes participaban: todos éramos parte del mismo experimento colectivo. Sin embargo, como suele ocurrir con este tipo de coaliciones, los tiempos y espacios en los que nuestras trayectorias se cruzan varían, y el equipo organizador continúa sosteniendo el trabajo.

Un seminario inaugural de tres días

Nuestro primer encuentro se realizó en formato virtual durante tres días. Marcó el inicio formal del seminario y fue también la primera oportunidad para vernos, aunque solo fuera a través de pantallas. El Dr. Ulises Moreno-Tabárez abrió con una conferencia sobre la espectralidad como método, inspirada en su trabajo etnográfico sobre los rituales del agua en la Costa Chica. La charla no buscó ofrecer respuestas, sino abrir un espacio de reflexión compartida. Pronto surgieron preguntas: ¿qué significa trabajar con espectros?, ¿cómo se traduce esa noción en nuestras propias disciplinas?, ¿qué lugar ocupa la ausencia en la investigación?

Figura 1. Capturas de pantalla de los talleres iniciales para presentar la serie de seminarios. Hubo alrededor de 40 personas presentes, pero la grabación solo muestra a quienes tenían la cámara encendida. Capturas de pantalla: Ulises Moreno-Tabarez.

Después de esa introducción, pasamos a los aspectos logísticos. Cada participante presentó una breve descripción de su trabajo actual y, a partir de esas afinidades temáticas, formamos diez equipos de tres personas. Las combinaciones fueron tan diversas como los temas mismos: desde el urbanismo extractivo y los saberes agroecológicos hasta la racialización urbana, la gestión de desastres y la planeación desde abajo.

Primeros trazos de trabajo

Algunos grupos encontraron rápidamente su propio ritmo. Comenzaron a escribir, intercambiar ideas y diseñar sus entregables. De esos esfuerzos iniciales surgieron proyectos que ya muestran una dirección clara: un manual de etnografía virtual para jóvenes investigadores que trabajan con comunidades costeras documentando su relación con los manglares; una iniciativa sobre salud pública y prácticas zootécnicas urbanas; debates sobre nuevas leyes ambientales y reformas constitucionales; relatos y ensayos que exploran el duelo urbano después de los huracanes; y un archivo digital colectivo que poco a poco va tomando forma como una plataforma regional para la red.

No todos los grupos avanzaron al mismo ritmo. Algunas conversaciones se diluyeron por falta de tiempo o de coordinación, mientras que otras necesitaron más acompañamiento para consolidarse. De los treinta participantes originales, veintidós continúan activos, un número alto si consideramos que, según nuestra experiencia, grupos de este tipo suelen reducirse a cifras de un solo dígito. Hemos sido deliberados en insistir en el trabajo en equipo, aunque la colaboración no sea la fortaleza de todos. Sin embargo, este es precisamente el núcleo de la construcción de redes: aprender a trabajar colectivamente, compartir responsabilidades y pensar en conjunto. Siempre habrá tiempo para el trabajo individual, pero esta red no es ese espacio. Confiamos en la autonomía como principio, aunque pronto comprendimos que la autonomía por sí sola no bastaba. La red necesitaba un pulso compartido, un momento para volver a encontrarse y reconocerse.

Entre la presencia y la ausencia

En esta sección, dos de nuestros espectros, ambas doctorandas con trayectorias distintas, comparten fragmentos de su experiencia dentro de la red de Espectralidades Afroindígenas.

Desde Acapulco, Astrid Paola Chavelas López escribe desde el territorio. Su texto, Los espíritus que habitan las piedras, se lee como una entrada de diario de su trabajo de campo en la costa, donde ella y su equipo desarrollan un proyecto autogestionado como parte de esta serie de seminarios. Su prosa se mueve entre la observación etnográfica y el gesto poético, trazando cómo el paisaje mismo se convierte en un archivo de espíritu, pérdida y persistencia.

Por su parte, desde la Ciudad de México, Ivette Salinas Carranza reflexiona sobre las posibilidades y los límites de la colaboración virtual, ofreciendo una mirada íntima sobre lo que significa trabajar colectivamente a través de pantallas, husos horarios y accesos desiguales. Sus palabras hablan de la paciencia y el cuidado necesarios para sostener una sensación de presencia cuando los cuerpos permanecen dispersos. Juntas, estas dos voces nos acercan al pulso de la red, que se despliega entre la distancia y la cercanía, entre lo visible y lo que aún está en formación.

Los espíritus que habitan las piedras – Astrid Paola Chavelas López

Es agosto, final de trimestre. Volví al puerto después de cruzar la ciénega hasta el mar. Luego, otra geografía, otra costa que se abre ante el asombro de cómo se construye la disidencia sobre lo cotidiano, cómo se diluye la tranquilidad de la tarde en la red de la hamaca, cómo se teje el duelo sobre los espacios. A lo lejos, la voz del arroyo canta su verdad entre las piedras. Las mujeres buscan sombra bajo el tamarindo mientras asolean la ropa limpia; las niñas y los niños juegan, brincan, renacuajos que se saben libres y salvos en su entorno. (ver Figures 2, 3)

Figura 2. Una familia disfrutando del río, fotografía de Astrid Paola Chavelas López.

Figura 3. Mujer secando la ropa en las rocas, fotografía de Astrid Paola Chavelas López.

La lluvia reverdece sobre el paisaje urbano litoral. El calor hiere el océano. En San Isidro, la tormenta tropical Erick y las variaciones de la luz hacen estragos en la producción casera de mezcal de la señora Mayte. El verano arrastra las nubes; sobre el océano se condensa la furia del relámpago. El lugar seguro se vuelve un barco que naufraga frágil entre el río de piedras.

El territorio habla. Pronuncia el lenguaje de los espíritus que lo habitan. Sobre las calles, los estragos. El fenómeno social se extiende más allá de los montones de escombros, lámina y tierra. Una urbe calcinada reposa ante la paciencia de la hierba. (Ver Figure 4)

Figura 4. Camioneta abandonada en la calle, fotografía de Astrid Paola Chavelas López.

Es tiempo de sandías. Montones de frutas criollas se forman sobre las aceras. La charla se cuela entre las preguntas. Los espectros. Lo que fue, lo que estuvo. Lo que permanece.

El cumpleaños de Rodrigo coincide con la fecha que guarda este calendario personal. Su ombligo se desprendió el día que la fuerza de trescientos kilómetros por hora vertió su furia sobre la precariedad de años. El sistema de salud rural es una metáfora compleja.

El silencio teje las respuestas ante el octubre que arrancó los carrizos de la tierra. El arroyo sobre la calle principal. Fe que se hinca ante la tormenta. La esperanza es un niño de ojos grandes. Ombligo de agua que lo vincula con su tona. De grande será la voz del arroyo. Las piedras guardan la fuerza del espíritu que sostiene su hogar.

Ivette Salinas Carranza — Ciudad de México

Participar en la construcción de la red Espectralidades Afroindígenas en formato virtual ha sido tanto enriquecedor como desafiante. Hay momentos en que los problemas técnicos, como los cortes de luz o la inestabilidad del internet, interrumpen nuestra comunicación, pero a pesar de ello hemos logrado mantener vivo el intercambio y el trabajo colectivo.

Desde la distancia, he aprendido a valorar la colaboración como una forma de presencia extendida, donde cada aporte, por pequeño que sea, forma parte de un tejido compartido. Trabajar en espacios virtuales también implica enfrentar los límites del tiempo y la energía, que no siempre coinciden. Sin embargo, hay momentos de conexión que me recuerdan que una red no se construye solo a través de la proximidad física, sino mediante el cuidado, la atención y la escucha.

La tecnología ha sido una herramienta importante que nos permite conectar desde distintos lugares y sostener este proceso. La diversidad de personas y trayectorias ha ampliado nuestras perspectivas, enriqueciendo el trabajo colectivo.

A lo largo de estos meses se han formado vínculos con peso académico, político y afectivo. Sorprende cómo surgen afinidades incluso sin conocernos en persona, cómo podemos articular preguntas y experiencias compartidas a pesar de la distancia. Este proceso me ha mostrado que el trabajo colectivo no siempre requiere presencia física para sentirse real o transformador.

Ahora espero con entusiasmo el encuentro presencial, poder hablar y escucharnos sin pantallas, tener conversaciones que no estén limitadas por el tiempo o la conexión. Espero que esta reunión nos ayude a consolidar la confianza, aclarar las direcciones y abrir nuevas posibilidades de colaboración. La presencia física de los demás, creo, fortalecerá lo que ya hemos comenzado a construir juntos.

Repensar el formato

Estas reflexiones nos llevaron a reconsiderar nuestra estructura. Originalmente, el plan era tener un encuentro presencial al inicio, luego trabajar de manera virtual hasta la reunión final en diciembre. Pero pronto se hizo evidente que, sin una coordinación constante y un tiempo compartido, la red corría el riesgo de fragmentarse. Decidimos entonces cambiar el rumbo. En lugar de esperar una participación virtual continua, organizaremos un encuentro presencial en Acapulco, un espacio para reunirnos, reconectarnos y fortalecer la red regional que poco a poco hemos venido construyendo. Este encuentro también permitirá a los participantes conocer los paisajes costeros que anclan nuestro trabajo teórico: los mismos lugares donde convergen urbanización, ecología y memoria.

Este encuentro no es solo logístico. Es metodológico. Lo entendemos como un gesto de cuidado, una oportunidad para transformar nuestras conversaciones dispersas en una práctica colectiva, para dejar que la red respire y crezca.

Al acercarnos a diciembre, sabemos que el éxito del proyecto no se medirá solo por los resultados, sino por las relaciones que perduren. Si lo espectral nos ha guiado hasta ahora, quizás sea porque este tipo de colaboración —extendida entre la presencia y la ausencia, entre la teoría y el territorio— siempre estuvo destinada a aparecer, desvanecerse y regresar de formas inesperadas.

Blog 2: Espectralidades en común: conjuraciones territoriales de presencia y memoria

Previa: Reimagining Urban Design Through the Pedestrian’s Lens