A voice from the peripheries

In 2017, Marielle Franco wrote a brief essay about the right-wing political wave growing in Brazil. Franco — black, gay, female, and from the favela of Maré in Rio de Janeiro — had been elected in Rio’s 2016 municipal elections as a city councilor representing the Party of Socialism and Freedom (PSOL). In this urgent, prescient essay, she described a “conjuncture, which favors Bonapartism or the rise of conservative authoritarianism.” She wrote with a clear-eyed view from the social peripheries of a city increasingly governed in practice by a combination of illicit crime organizations and elements of formal political institutions and police.

Three months after the publication of this essay, Franco was found shot dead in her car from an apparent targeted assassination. She was on her way home after participating in a public round-table discussion about “young black women moving power structures,” and in recent months she was increasingly outspoken about the murders of young black people in favelas at the hands of police and shadowy “militias.” Her assassination highlighted the extent to which the basic promise of democracy — political equality — is mediated through a dense web of inequalities of identity and place.

Franco’s murder and the subsequent election of Jair Bolsonaro underscored the possibility of a coherent conservative authoritarianism that crossed cultural, social, and economic dimensions of political life. However, I argue that Franco’s view from the periphery illuminated something more like a narrow Bonapartism — a charismatic authoritarian style marked by selective appeals for order. Bolsonaro has often been cast in the role of “Trump of the Tropics,” a quintessential political figure of “law and order.” But the Bolsonaro phenomenon does not represent a yearning for an impersonal order of law. Instead his rise is about a restoration of the social, economic, and spatial orders of the past.

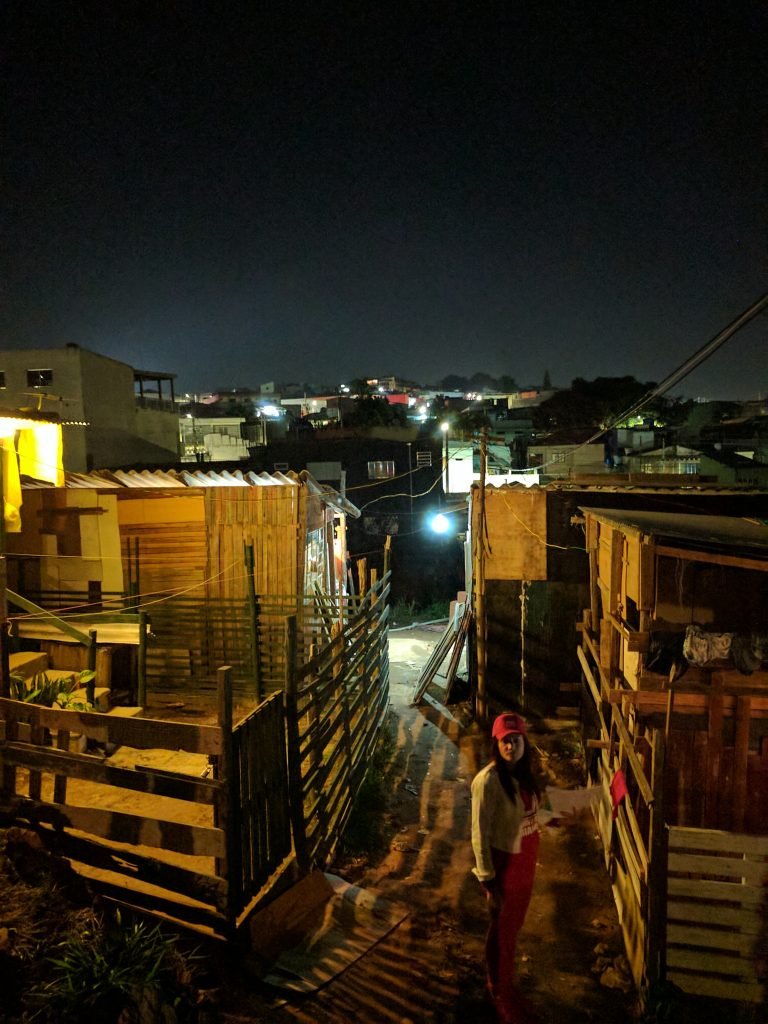

A new land occupation organized by the Front for the Housing Struggle (FLM) rises in the eastern peripheral neighborhood of Guianazes, São Paulo. Photo: Benjamin H. Bradlow, 2017.

With comparative perspective, it is now increasingly clear that the right-wing authoritarian style thrives on inequalities both between and within places. The rise of Donald Trump in the United States is commonly associated with an increasing divergence of fortunes between upwardly and downwardly mobile cities and towns. Similarly, voting patterns for and against Brexit in the United Kingdom had a strong correlation to regional divergence. The geographer Christophe Guilluy arguably predicted the emergence of the ongoing “yellow vest” movement in France in his analysis of the spatial separation of metropolitan elites in “new citadels” that have increased the social and economic distance from the country’s smaller cities and towns.

The connections between the divisions of place and the authoritarian style in politics that Franco noticed in her 2017 essay, shortly before her murder, burst into view as Bolsonaro’s presidential campaign grew more popular over the course of 2018. His election has generally been subject to explanations of national-level political dynamics: corruption scandals, declining security, and economic recession. Likewise, the characteristics of Bolsonaro’s voters have been explained using aggregated social and economic categories: wealth, income, occupation, education, race, gender.

I contend that an urban perspective allows us to make sense of how these structural identities of class, race, and gender intersect through the geography of place to drive the rise of this right-wing Bonapartism. I define this “urban perspective” in two ways: First, a relational view of differences between places; and second, a focus on the role of local institutional dynamics in driving places apart.

The democratic basis for a conservative restoration

The fundamental challenge of explaining a democratic turn to the right-wing authoritarian style in a country like Brazil is that a purely demographic analysis is insufficient. In such an unequal society, there is no conceivable political majority comprised of the wealthy, well-educated, and professionalized classes. And yet, Bolsonaro, a seeming avatar of a white, wealthy, and patriarchal worldview came close to a first-round victory with 46% of the vote. He ended up running away with a clear margin of 10% in the second round run-off against former São Paulo mayor Fernando Haddad of the Worker’s Party (PT). A base of rich white males may be a strong core of political support. However, a more complex set of factors has to be mobilized in order to explain his winning political majority.

The emergence of what I call “political peripheries” explains the mix of economic, cultural and spatial factors that led to Bolsonaro’s election. The contradictions of this coalition help explain why his governing style in his first few months as president appears more “Bonapartist” than a programmatic, “conservative authoritarian” style. Though he and his political allies often threaten to destroy “the old politics,” Bolsonaro’s vague political project is primarily a social restoration. He consistently contrasts the “good citizen” (cidadão de bem) against the “bandit” (bandido). This latter category recalls the long-standing Brazilian trope of the “malandro” as a social impurity that 20th century authoritarian governments mobilized as necessary to flush out of the Brazilian body politic.

Returns from both the first and second round of voting show that in major cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, it was not just wealthy areas that propelled Bolsonaro to victory. While these were his areas of strongest support, he was able to turn sufficiently large segments of poorer neighborhoods that had previously voted consistently for the PT to support his candidacy.

Likewise, regional dynamics across the country exhibit similar effects. While centers of industrial working class activism in southern and southeastern regions were the PT’s initial base of support in the 1990s, it rose to national power by breaking through to more rural poor populations in the country’s north and northeast. At the more aggregated scale of the region, returns from the 2018 second round election told a simple tale of two countries: The wealthier more industrialized south voted for Bolsonaro, while the poorer and more rural north voted for Haddad. But again, Bolsonaro got sufficient minority support from the regions that did not vote for him, which minimized the damage.

As economist Laura Carvalho has shown, the segment of voters earning between two and five times the national minimum wage was a key swing voting bloc for Bolsonaro. Many of these voters live in the peripheries of large cities. They are materially better off than the rural poor who arguably gained the most under PT rule, but are still socially distant from the traditional elites of the urban cores. And their employment prospects were most vulnerable to the doubling of formal unemployment in the deep and lengthy recession that began in 2014.

A housing project in the northern neighborhood of Jaraguá, São Paulo. The project was funded through the federal government’s My House My Life low-income housing subsidy and managed by the Federation of Housing Movements (UMM). Photo: Benjamin H. Bradlow, 2017.

An urban perspective

All of this suggests that an explanation that flattens class, space, and ideological alignment (i.e. poor places vote for the left, rich places vote for the right) falls short. Instead, place is a social dimension in which politics come alive– hence, “political peripheries.” Perry Anderson recently argued that Bolsonaro’s victory represents a shift in the political center of power from São Paulo, the historic home of the industrial workers who brought the PT to power, to Rio de Janeiro, home to earlier generations of Brazil’s bourgeois elites. A brief comparison of these two cities illustrates why the emergence of new “political peripheries” matters.

In São Paulo, the past thirty years have seen a slow, but unmistakable breaking down of the dynamic of a wealthy core and poor periphery. According to recent studies that make use of national and municipal census data, the portion of the city’s households located in informal settlements rose slightly — from 9.2% in 1991 to 11.6% in 2010 — but access to sanitation for informal settlement households improved significantly, rising from 25.1% in 1991 to 67.9% in 2010. A bus system that previously serviced peripheral neighborhoods through a mix of irregular informal and formal operators has become integrated and more elaborated. Roads that were once reserved for the exclusive use of middle class private car owners now have lanes reserved for public buses. Furthermore, the most authoritative recent studies of segregation have noted an increasing heterogeneity of neighborhoods and a loosening of the sharp boundaries that have long characterized the city’s social world.

In Rio de Janeiro, the growing role of militia and gang governance, that Franco highlighted as an activist and politician, hardened the boundaries between poor and wealthy neighborhoods. Poor neighborhoods were neglected by municipal authorities. For example, my analysis of national census data shows that slightly more than 1 in 5 households in the city is located in an informal settlement. Many local politicians and officials have been arrested in investigations related to the national “Car Wash” corruption case, often due to skimming off the top of large infrastructure projects related to the World Cup and Olympics.

Bolsonaro’s dualistic view of the “good citizen” and the “bandit” underpinned a political appeal to restore order and realize his campaign’s slogan: “Brazil above all. God above everything.” In São Paulo, the softening of geographic boundaries in the city entailed an upheaval in social relations. Spaces of conspicuous consumption, from shopping malls to airports, were now available to social groups that were previously marginalized — especially those who were poor and black. As new economic recession and long-term deindustrialization in the city began to hit ordinary households, a sense of disorder grew even despite the relatively low crime rate in São Paulo. My research on the recent history of the city’s municipal institutions shows that a lengthy, movement-led project of municipal state-building had begun to ossify into a more bureaucratized and elite-led project under Haddad, the city’s PT mayor from 2013-2016. He would ultimately challenge Bolsonaro in 2018. A recent analysis by geographer Matthew Richmond found that of the 23 peripheral electoral zones that voted for the PT in the presidential run-off in 2010, only six voted for the PT in 2018.

In Rio de Janeiro, we see an opposite mechanism with a parallel outcome: the hardening of peripheral boundaries (even for those slums that were physically close to the center of the city) and a declining public security situation fed into the hunger for order. Richmond’s analysis in Rio de Janeiro found that in 2014 almost all peripheral voting zones supported the PT, but the PT did not win a single zone four years later.

The contrast between these two cities helps us perceive that local institutional action, especially at the municipal scale, mattered deeply for the everyday lives of city residents. And yet, in both cases Bolsonaro was able to peel off voters on the poor peripheries to construct a winning political coalition. In these two cases, institutional changes (the increased capacity and will in São Paulo to address the peripheries and precisely the opposite in Rio de Janeiro) produced contrasting upheavals that could not be contained in the face of national economic and political crisis.

A land occupation organized by the Front for the Housing Struggle (FLM) in the northern periphery of São Paulo, near Brasilândia. Photo: Benjamin H. Bradlow, 2017.

Now, Bolsonaro’s reliance on his social media-driven charisma to reign in Brazil’s uneven welfare state typifies his brand of Bonapartism. The restoration he promises would harden the divide between Brazil’s multiplicity of cores and peripheries.

The PT and a diverse range of social movements and unions helped build a relatively durable political basis for the achievements of Brazil’s welfare state. Today, political parties and social movements are adjusting to the reality of a new political climate, playing both offense and defense against Bolsonaro’s right-wing wave. But the longer-term path forward is clear. A project to undo the now-deepening inequalities of both social power and material resources will need to be one with an “urban perspective.” It will have to be capable of wielding public institutions of the state that can channel popular movements to overcome the peripheries that define Brazilian political life. Franco ended her essay with a clarion call to “center as social actors those from the margins and the favelas throughout Brazil. Building structures that help empower poor, black women to take on the role of active citizenship, aimed at winning a city of rights, is fundamental for the revolution the contemporary world requires.”

Over the past three decades, the democratic project in Brazil has haltingly, and unevenly, aimed to overcome these political peripheries. Bolsonaro aims to restore them.

Ben Bradlow is a Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology at Brown University. He works in the areas of Urban Sociology; Political Sociology; Political Economy of Development and Globalization; and Comparative-Historical Methods. His dissertation, titled Urban Origins of Democracy and Inequality, is a comparative-historical investigation of urban institutions governing public goods in São Paulo in Brazil and Johannesburg in South Africa.

All essays on Political Geographies of Right Wing Populism

Introduction

Liza Weinstein

Spatial Configurations of Right-Wing Populism in Contemporary Germany

Nitzan Shoshan

Waiting for Duterte

Marco Garrido

Brazil’s Political Peripheries and the Authoritarian Style

Benjamin H. Bradlow

Regional Liberals and the Urban Anxieties of Indian Populism

Mona G. Mehta

The Contested City as a Bulwark against Populism: How Resilient is Istanbul?

Berna Turam

Related IJURR articles on Political Geographies of Right Wing Populism

‘Get out of Traian Square!’: Roma Stigmatization as a Mobilizing Tool for the Far Right in Timişoara, Romania

Remus Creţan Thomas O’brien

Revitalizing the City in an Anti‐Urban Context: Extreme Right and the Rise of Urban Policies in Flanders, Belgium

Pascal de Decker, Christian Kesteloot, Filip de Maesschalck and Jan Vranken

Using the Past to Construct Territorial Identities in Regional Planning: The Case of Mälardalen, Sweden

Luciane Aguiar Borges

Le Pen’s comeback: the 2002 French presidential election

Nonna Mayer

The Urban Politics and Subject Formation

Lisa Hoffman

How Globalization Really Happens: Remembering Activism in the Transformation of Istanbul

Christopher Houston

The Postcolonial City and its Displaced Poor: Rethinking ‘Political Society’ in Delhi

Sanjeev Routray

The Ideology of the Dual City: The Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila

Marco Garrido

How Interspersion Affects Class Relations

Marco Garrido

The Citizen Participation of Urban Movements in Spatial Planning: A Comparison between Vigo and Porto

Miguel Martínez

Hamburg’s Spaces of Danger: Race, Violence and Memory in a Contemporary Global City

Key Macfarlane & Katharyne Mitchell

Experiences of Urban Militarism: Spatial Stigma, Ruins and Everyday Life

Silvia Pasquetti

© 2019 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.