In India, as elsewhere, the 21st century age of populism has crystallised in the immediate context of the global economic crisis of 2008-2009, triggered by rampant neoliberal capitalism. The emergent populist discourse calls for the demolition of the old political order accused of corruption. The universal populist theme of ‘corrupt elites’ versus the ‘moral people’, which operates on emotive antagonisms and anxieties about societal plurality and economic inequalities dramatically heightened in the present era (Müller 2016), is very much present in India (McDonnell and Cabrera 2019). Here too, populism has shown a tremendous affinity for electoral politics where the ‘popular mandate’ is sought and flaunted because of the democratic legitimacy it bestows on the populist ruler. Just like in other parts of the world, rising anti-intellectualism in India is directed against intellectuals specifically espousing liberal and secular values. Populist slogans such as “Hard work not Harvard” (PTI 2017) reduce Harvard to a pejorative that stands in for English speaking liberal elites who are seen as having undeservedly dominated the Indian establishment since independence because of privilege rather than merit. Populism’s ideological neutrality allows it to be appropriated by groups across the ideological spectrum. Hindu nationalists have deployed populism as an electoral device to polarise society and secure ‘popular mandates’.

Despite these surface similarities with the global rise of populism, I argue that present-day right wing Hindu nationalist populism has historical specificities that make the Indian case unique. The distinctiveness of Indian populism turns on the category of the ‘urban’ and its particular relationship with elites. Urban elites are the central targets of the populist campaign in India, but a deeper analysis of this campaign reveals a duality and deception that lays bare the anxieties and political objectives that drive Hindu nationalist populism. The ‘urban’ is not limited to a geographically fixed space that is pitted against the rural, but operates as a political category and cultural metaphor signifying the elements of aspiration, political contestation and derision. In the West, the urban is the site of immigrant influx and hence a breeding ground of xenophobia and fear (of loss of economic opportunities) among working class citizens (Rossi 2018). In contrast, Indian populism does not primarily emerge from the societal fear and flux caused by immigration. The urban landscape in India is a site of neoliberal aspiration for all, which is sold as the ‘development dream’ packaged with Bullet Train projects, Smart City missions, and urban place-making initiatives (Desai and Sanyal 2011).

Two types of urban elites

Unlike the Western populist derision of urban elites for their support of multiculturalism and immigrants (Rossi 2016), the anti-elite discourse in India is more nuanced in that it is directed at two distinct types of urban elites. Both groups of elites can be considered urban liberals, broadly speaking, but each group shares a particular relationship with the urban and the non-urban, which ultimately determines the distinct reactions of Hindu nationalists towards the group. I draw on analyst Sugata Srinivasaraju’s typology of two types of liberals, to call the first type of elites ‘English liberals’, and the second group as the ‘regional liberals’ (Srinivasaraju 2019). Populists ridicule the ‘English liberals’ as belonging to ‘Lutyens Delhi’ and the ‘Khan Market gang’ (Indian Express New service 2019). ‘Lutyens Delhi’ refers to British colonial era architectural buildings (named after British architect Edwin Lutyens who designed them) that house the residences and offices of the highest ranking politicians and bureaucrats. Located within the Lutyens precincts is Khan market, which emerged as a partition era refugee centre and has since developed into an elitist market with gourmet restaurants and designer stores. Together these places in the national capital have become the reigning metaphors of urban elitism at large. They have been associated with the English speaking liberal elites who have dominated the mainstream media as prime-time journalists, commentators and public intellectuals, led universities and think-tanks and occupied powerful positions in the upper echelons of the bureaucracy and government since Indian independence.

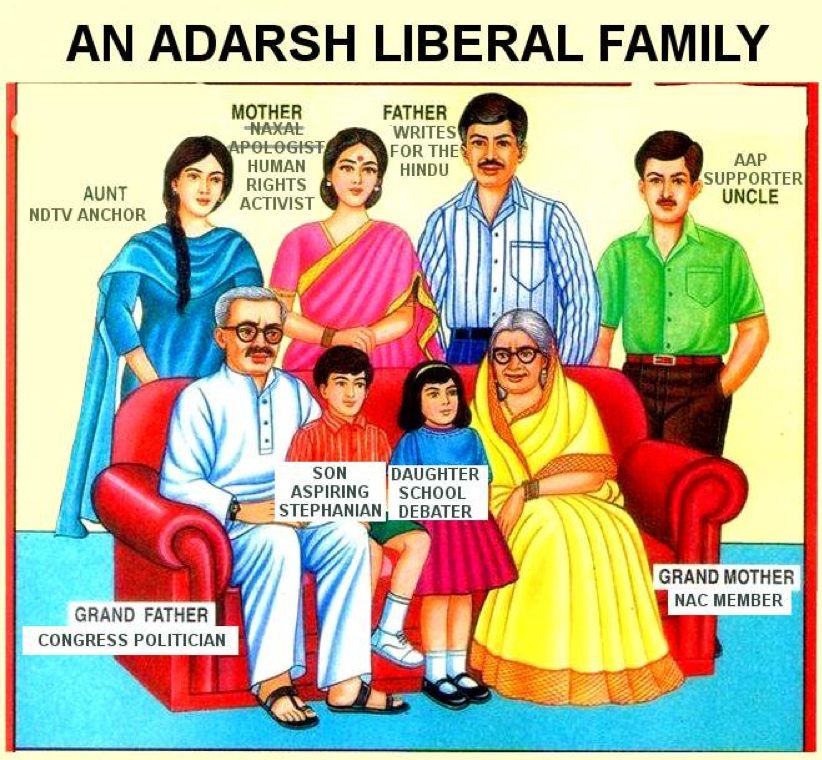

The Hindu nationalist parliamentary election campaigns of 2014 and 2019 unleashed a scathing populist attack on ‘English liberals’ as the enemies of the people. In addition to being accused of corruption, these elites were scorned for claiming to champion the liberal ideals of the Indian Constitution while being culturally westernised, out-of-touch with grass-roots/rural India, lacking facility in regional languages, and being ashamed to embrace the dominant Hindu Brahmanical culture. The image below circulating on social media is a sarcastic populist representation of a typical ‘English Liberal’ family that is well entrenched economically and politically in the Delhi establishment. For instance, the ‘Mother’ in the image, dressed in ethnic Indian garb is only superficially Indian because she is a champion of human rights, considered by Hindu nationalists as a Western import. The association of the rights discourse with westernization is an especially common trope in the populist narrative. It is meant to indicate the hypocrisy and rootlessness of the ‘English liberals’. The depiction of the ‘Son’ as an ‘aspiring Stephenian’ refers to the famous St. Stephens liberal arts college in Delhi, that has produced a steady stream of prominent English speaking elites.

A populist representation of a quintessential family of ‘English Liberals’ from

Lutyens Delhi. Adarsh means ‘model’ or ‘ideal’ in Hindi. Source: https://twitter.com/adarshliberal

Fear of Regional Liberals

Despite a relentless campaign against the ‘English Liberals’, this group is not the real threat to the political objectives of Hindu nationalism. The visible nepotism and corruption of the ‘English liberals’ have made them easy targets for generating the ‘elites versus the people’ narrative that populists thrive on. But their scapegoating is largely a tactic and diversion to mask the real threat from the second type of ‘regional liberals’. Populists consider this second type of urban elites so dangerous that they have bestowed upon them the derisive epithet of ‘Urban Naxals’. Who are the regional liberals? And why do they pose a far more serious threat to Hindu nationalists? The ‘regional liberals’ seamlessly straddle the urban and rural areas and communicate fluently in regional Indian languages. Unlike the limited social reach of ‘English liberals’, whose influence does not go beyond urban pockets and the exaggerated clamour of social media, regional liberals enjoy a grassroots following in big cities, small towns and villages. Their social reform activism, such as campaigns against superstition and caste atrocities, promotion of Hindu-Muslim communal harmony, fight for gender justice and popular writings and publications in regional languages have given them a mass following in both urban and mofussil India. As successful medical doctors, university vice chancellors, scholars, journalists and national award-winning writers, these ‘regional liberals’ are every bit as professionally accomplished elites as the ‘English liberals’, but far more connected with the people.

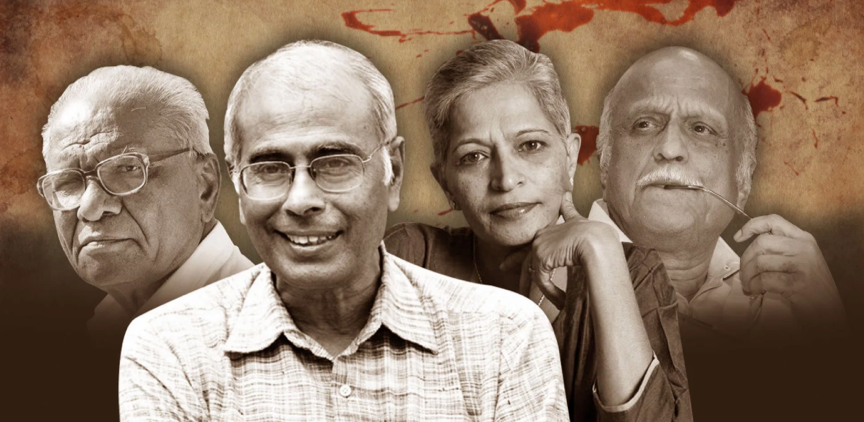

A collage of regional liberals murdered by conservative groups in recent times. From left to right, they are Govind Pansare, Narendra Dabholkar, Gauri Lankesh and MM Kalburgi. Source: newsclick.in

The slain rationalist and medical doctor Narendra Dabholkar, labour organiser and human rights activist Govind Pansare, the Kannada language poet-academic and Lingayat social reformer MM Kalburgi, and anti-caste writer-activist and publisher of a popular Kannada language tabloid Gauri Lankesh were the very epitome of ‘regional liberals.’ Their brutal murders between 2013 and 2017 by conservative groups attest to the threat their written works and social engagement posed to the hegemonic social order in Hindu society (Malekar 2016). The term ‘Naxal’ in South Asia is often used interchangeably with ‘Maoist’, and refers to citizens who operate in some of the most remote and deprived tribal areas and are engaged in a violent insurgency against state agencies to demand social justice. Contrary to espousing a violent subversion of the state, ‘regional liberals’ work within mainstream civil society and the political establishment to secure greater state accountability and social justice. For instance, for years rationalist Narendra Dabholkar was a crusader for reforming the law against superstition which was ultimately passed by the state government soon after his murder in the form of ‘The Maharashtra Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifice and other Inhuman, Evil and Aghori Practices and Black Magic Act, 2013’. The Hindu nationalist use of the prefix ‘urban’ as an adjective to describe ‘Naxals’—known to typically operate in remote tribal hinterlands—is noteworthy. This intentionally ironic nomenclature of ‘Urban Naxal’ is meant to index the potential for social destruction by regional liberals and simultaneously provide the moral justification for arresting and violently targeting those identified as such. The ability of the regional liberals to successfully engage with the working classes in urban and rural areas rattles Hindu nationalists, who fear the loss of cultural hegemony over the existing social order.

The political formations of Hindu nationalists have traditionally enjoyed the support of the urban middle classes, with an electoral base predominantly consisting of petty traders and small businessmen from upper and intermediate Hindu caste groups. The economic boom following the liberalization of the Indian economy in 1991, and decades of affirmative action policies for hitherto marginalised castes have together unleashed definite demographic shifts. Specifically, these changes have led to the expansion of an aspirational middle class beyond the upper castes and metro cities to tier-two cities, small towns, semi-urban and rural villages. According to the 2011 census, 32 per cent of India is urban and 68 per cent is rural. Although their precise numbers are difficult to estimate, according to one study, 46 per cent of rural residents in India self-identify as ‘middle class’ (Kapur, Sircar and Vaishnav 2017). In addition to the working classes, ‘regional liberals’ also enjoy a following among this growing aspirational middle class in small town and rural India. In order to succeed electorally, it is imperative for Hindu nationalists to expand their following beyond urban India. Hindu nationalists thus find themselves in direct competition with ‘regional liberals’ in their attempts to expand their influence and cultivate support among the non-urban middle classes.

Tactical use of populism by Hindu nationalists

The two-pronged anti-elite discourse of Hindu nationalist populism has played a big role in the electoral decline of the Indian National Congress party (INC). Historically associated with MK Gandhi’s nationalist movement against British colonial rule, the Congress in recent years has become the ultimate symbol of the elitist old order. The Nehru-Gandhi family that has controlled the party, is increasingly reviled as the self-promoting political dynasty standing in the way of the people’s national interest. In its place, the Hindu nationalist populists claim to represent the real interests and voices of the Indian people. They promise to inaugurate a ‘New India’ that is ‘Congress- mukt’ (free), unashamed to take aggressive pride in the dominant upper caste Hindu culture, and willing to call into question the national loyalty of India’s Muslim minorities (Kaul 2017).

Interestingly, the Hindu nationalist claim of a ‘New India’ is hardly new and reflects an older early 20th century political battle between two competing ideas of India. In this battle of ideologies, the liberal, democratic and secular idea of India won out and got enshrined in the Indian Constitution. The idea that got politically marginalised was the Hindu nationalist notion of Hindutva, that espoused the ‘two-nation theory’ about inherent Hindu-Muslim animosity and the superiority of upper-caste Hindu cultural dominance. However, Hindutva continued to lurk in Indian civil society in the seven decades after independence, promoted through a network of right wing grassroots organisations. Although the Hindu nationalist idea of a ‘New India’ is not new, what is new is its use of populism as a tactic to gain political power. This is because populism is not so much a political ideology or a coherent set of policies, but a political logic of sorts (Judis 2016). In recent years, Hindu nationalists have found in populism a powerful weapon to legitimize and hoist their longstanding idea of India within the framework of parliamentary democracy.

Historically speaking, MK Gandhi was arguably the most prominent ‘regional liberal’ in modern India with a mass following that cut across the urban and rural. When Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress, the party resembled an exclusive elite club with almost no presence beyond small urban pockets. He transformed it into a mass movement that involved the individual self, communities and civil society. Using traditional Indian idioms and drawing on the sub-continent’s pluralist religious traditions, Gandhi’s project of Indian independence was as much about challenging existing inequalities of caste, gender and class as it was about gaining political independence (Mehta 2017). This project posed a serious challenge to the traditional structures of upper caste privilege in Hindu society, of which the Hindu nationalist elites had been beneficiaries. The killing of Gandhi at the hands of a Hindu nationalist was a testament to the fear of Gandhi’s influence and position as a regional liberal who was rooted within and operated across the categories of the urban and rural. Ultimately, the political ‘Other’ of Hindu nationalist populism is neither ‘immigrants’, nor ‘Muslims’, despite the obviously overt hostilities towards religious minorities, but ‘regional liberals’ who are committed to an emancipatory and egalitarian vision of Hindu society.

Mona G. Mehta is Assistant Professor in the department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Gandhinagar, India. Her research interests include democracy and identity politics and urban transformations in India. She is currently working on a book manuscript that examines the processes of urban marginality, mobility and youth aspirations across urban and peri-urban spaces. She has co-edited, Gujarat Beyond Gandhi: Identity, Conflict and Society(Routledge 2010) and several research articles.

All essays on Political Geographies of Right Wing Populism

Introduction

Liza Weinstein

Spatial Configurations of Right-Wing Populism in Contemporary Germany

Nitzan Shoshan

Waiting for Duterte

Marco Garrido

Brazil’s Political Peripheries and the Authoritarian Style

Benjamin H. Bradlow

Regional Liberals and the Urban Anxieties of Indian Populism

Mona G. Mehta

The Contested City as a Bulwark against Populism: How Resilient is Istanbul?

Berna Turam

Related IJURR articles on Political Geographies of Right Wing Populism

‘Get out of Traian Square!’: Roma Stigmatization as a Mobilizing Tool for the Far Right in Timişoara, Romania

Remus Creţan Thomas O’brien

Revitalizing the City in an Anti‐Urban Context: Extreme Right and the Rise of Urban Policies in Flanders, Belgium

Pascal de Decker, Christian Kesteloot, Filip de Maesschalck and Jan Vranken

Using the Past to Construct Territorial Identities in Regional Planning: The Case of Mälardalen, Sweden

Luciane Aguiar Borges

Le Pen’s comeback: the 2002 French presidential election

Nonna Mayer

The Urban Politics and Subject Formation

Lisa Hoffman

How Globalization Really Happens: Remembering Activism in the Transformation of Istanbul

Christopher Houston

The Postcolonial City and its Displaced Poor: Rethinking ‘Political Society’ in Delhi

Sanjeev Routray

The Ideology of the Dual City: The Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila

Marco Garrido

How Interspersion Affects Class Relations

Marco Garrido

The Citizen Participation of Urban Movements in Spatial Planning: A Comparison between Vigo and Porto

Miguel Martínez

Hamburg’s Spaces of Danger: Race, Violence and Memory in a Contemporary Global City

Key Macfarlane & Katharyne Mitchell

Experiences of Urban Militarism: Spatial Stigma, Ruins and Everyday Life

Silvia Pasquetti

© 2019 THE AUTHOR. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH, PUBLISHED BY JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD UNDER LICENSE BY URBAN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS LIMITED

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.