‘To say we have defunded the police isn’t accurate, but

to say we have shifted the status quo is accurate.”

– James Burch, Policy Director of the Anti Police-Terror Project, 2021

On Saturday, 10 July 2021, two political rallies were held along the shores of Lake Merritt in Oakland, California. Both focused on the safety of Oakland’s residents, yet their visions of safety stood in sharp contrast. While one event was organized by the Anti Police-Terror Project (APTP), a “Black-led, multi-racial and intergenerational coalition who seek to eradicate police violence in communities of color”, the other event was, in fact, organized by the police.

When a police department itself organizes a political rally, what does this say about the ideological struggle at play in cities like Oakland? The counter-hegemonic push to defund the police in cities across North America since the uprisings of summer 2020 has pushed carceral ideologies into flux. And yet, dominant ideologies are always undergoing contestation, the media being one site where they are reinforced and re-configured. In what follows, I explore these two rallies that took place in Oakland in July 2021, considering what these events reveal about the ideological struggle over public safety currently underway in US cities and how they offer a window into how racial capitalism scaffolds urban space.

‘Remember George Floyd’ mural along Broadway in downtown Oakland. Photo: M.M. Ramírez, June 2020.

APTP’s event, “Re-imagine Safety: Community Celebration and Caravan”, was set to begin at 1pm at the corner of Lakeshore and Brooklyn, on the east side of the lake. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, APTP has been organizing car caravans as a form of protest that also allows for social distancing. On 31 May 2020, in a protest catalyzed by the police killings of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Breonna Taylor in Atlanta, and Steven Taylor in San Leandro, over 5,000 cars and hundreds of bicycles joined APTP’s caravan that wound around the city of Oakland, demanding justice. Using a radio signal that broadcast protest leader’s speeches to those participating, APTP called for the Oakland Police Department (OPD) to be defunded by 50%, a campaign they had been developing since 2015. In the weeks that followed, the DefundOPD coalition, made up of APTP and a dozen other Oakland community organizations, publicized policy recommendations of how the city could reduce the policing budget and “reinvest that money in alternative non-police programs that actually improve the well-being of our communities”.

On this Saturday afternoon over a year later, the “Re-imagine Safety” event was intended not as a form of protest but as a form of presence and celebration, for after six years of organizing, Oakland City Council approved the reallocation of $18.4 million intended for OPD’s operating budget to instead fund violence-prevention programs and mental health services. While this was a major win for the coalition, the $18.4 million to be re-directed was far less than the 50% DefundOPD coalition was calling for. In fact, City Council actually approved an increase of $9 million in police department spending, the two-year budget increasing from $665 million to $674 million. So while the OPD budget approved by City Council was $18.4 million less than what Mayor Libby Schaaf had proposed, police funding still increased overall.

‘Justice for Breonna Taylor’ mural and altar outside the Betti Ono Art + Community Space in downtown Oakland. Photo: M.M. Ramírez, June 2020.

Less than a mile from where APTP’s caravan was beginning, a second event was underway on the south side of Lake Merritt. Around 200 people gathered, many wearing white shirts that read “Stand Up for Safe Oakland”, calling for an end to gun violence after the city recorded 71 homicides in Oakland at the time of the rally in 2021. According to those participating in this rally, a safe Oakland required drastically different measures than those proposed by the DefundOPD coalition. The rally started off in a similar form to many of APTP’s rallies – honoring lives lost to violence – and yet the tone was markedly different, as OPD Police Chief LeRonne Armstrong offered up a narrative of how police couldn’t stop the violence on their own, how they needed community members to ‘unite’ to ‘bring peace to Oakland’. The participants then proceeded to march along the lake, ending in the same spot where APTP’s caravan began – at Lakeshore and Brooklyn, the site where Dashawn Rhoades was shot and killed at a Juneteenth celebration three weeks prior. Rhoades’ death had been highly politicized in the lead up to City Council’s budgetary vote, with Oakland’s Police Officers Association releasing a statement days after his death, stating: “the litany of violent crime victims has already demonstrated that Oakland’s ‘defund the police’ strategy has failed”.

What might be colloquially called ‘copaganda’ (Wood & McGovern 2020), it was no coincidence that the political rally “Stand Up for Safe Oakland” also harkened ‘safety’ in its title. The police chief’s decision to organize the rally on the same day, time, and site as APTP’s event clearly sought to recover the term ‘safety’ from community groups like APTP, who had been advocating ‘re-imagine public safety’ with a distinctly abolitionist frame. OPD’s rally received media coverage on all the local TV networks that evening, all of which reported a similar message: that Oakland’s homicide rate was on par with rates the city hadn’t seen in nearly a decade. Reporting on the rally was paired with footage of crime scenes, fireworks, and sideshows, associating these events with that of homicide, and according to local news channel NBC Bay Area, Oakland was “a city that’s had a violent reputation for decades”. This imaginary of Oakland as a violent, unruly place, initially borne of sensationalist media coverage of the Black Panther Party (Morgan 2006) and of urban renewal policy framings of Oakland in the 1960s (Roy & Crane 2015), has been having a resurgence in the media since the 2020 uprisings, a deeply racialized discourse has framed the city as a site in need of greater policing (Bradley 1993; Muhammad 2010).

Mural of the 7th point of the Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Program, along Broadway in downtown Oakland. Photo: M.M. Ramírez, June 2020.

The fact that APTP’s celebratory event did not receive media airtime, while the local news channels were quick to report on OPD’s rally, reminds us of how ideology works, “since the media’s main sphere of operations is in the production and transformation of ideologies” (Hall 2021: 100). OPD was clearly attempting to reclaim the term ‘public safety’ in its rally, pushing back against the APTP campaigns that associate the police with terror and violence. Carceral ideologies that render police and prisons a necessary component of public safety have been called into question in the US over the past decade (Taylor 2016; Rodriguez 2020), especially after 2020’s mass protests demanding the defunding of police departments and reinvestment in social services prompted these struggles to become more widely recognized and politically viable.

This shifting perception of the police, and the role that police and prisons play in US society, has altered the ideological terrain of the carceral state. As Stuart Hall theorized:

…ideology is a practice…it is generated, produced and reproduced in specific settings (sites) – especially, in the apparatuses of ideological production which ‘produce’ social meanings and distribute them throughout society, like the media. It is therefore the site of a particular kind of struggle… Ideological struggle represents an intervention in an existing field of social practices and institutions; those which sustain the dominant discourses of meaning of society. (Hall 2021: 102)

Local media’s mass-broadcasting of OPD’s rally and erasure of APTP’s event reinforces dominant discourses of the carceral state, yet also reveals how discourses of ‘public safety’ are in a space of ideological struggle. Returning to Hall, “certain ideological discourses do have or have acquired, historically, well-defined connections to with certain class places…these ‘traces’, as Gramsci called them, and historical connexions – the terrain of past articulations – are particularly resistant to change and transformation…new forms of ideological struggle can bring ‘old’ traces to life” (Hall 2021: 102-103). The imaginaries currently being reproduced in Bay Area media, television media in particular, which portray Oakland as a violent place in need of further policing are re-articulations, traces of imaginaries of the city that were dominant from the 1960s onward and that have shifted over the last decade as the city has gentrified (Ramirez 2017). While these discourses have never fully disappeared, they come into play when needed to scaffold the racial capitalist order of the city. In this case, these imaginaries of Oakland are being played and replayed to fend off alternative discourses of public safety that have emerged in the popular consciousness so as to re-stabilize the carceral state.

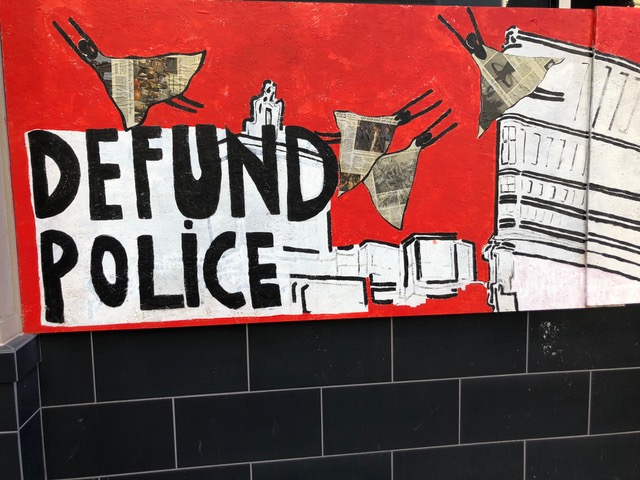

‘Defund Police’ mural along Telegraph Avenue in downtown Oakland. Photo: M.M. Ramírez, June 2020.

APTP’s re-imaginings of public safety threaten OPD, especially as community groups successfully redirected $18 million away from the police. In the US, the police function as a “specific incarnation of the state” (Bloch 2021: 2), whose structural role is “to maintain white supremacy and capitalism” (Wang 2018: 10). While in the dominant discourse of US society, the police’s role is to ‘protect’ public safety, it has been widely documented that the police disproportionately criminalize, use-excessive force upon, and kill Black lives (Cacho 2012; Taylor 2016; Maynard 2017). This hyper-criminalization of Black, Indigenous and other people of color is a function of racial capitalism, for, as Jackie Wang has found, “municipalities and states are increasingly dependent on the use of coercive extractive mechanisms that squeezed the people on the bottom for cash” (2018: 16). This is to say, the prison industrial complex is a value-producing mechanism that accumulates capital by detaining, arresting, fining, transporting, and caging humans (Gilmore 2007; Story 2019; Brooks & Best 2021).

To challenge the idea that police are an essential part of public safety, as DefundOPD has done, is to destabilize the mechanisms that hold racial capitalism together in US cities like Oakland. As Robin D.G. Kelley writes, “racial capitalism’s driving force was not the invisible hand of the market but the invisible fist of state-sanctioned violence” (2021: xiii); to defund the police, to abolish the prison industrial complex, an end goal of groups like APTP, would unsettle the very foundations of US society and economy. Dominant political, cultural and racial ideologies are always in need of recalibration to maintain hegemony. After the mass uprising of 2020 pushed public discourse into the realms of abolition, the hegemonic is now in a phase of correction. Media coverage of ‘crime waves’ has surfaced across the US. On a federal level, the Biden administration has chosen to address the issue by allowing states and local governments to draw from $350 billion coronavirus relief funds to hire more police officers. Funds that were designated to provide economic relief to people struggling across the US as a result of the instability and precarity brought on by this pandemic are now being earmarked by city governments to further police those most vulnerable to premature death.

‘Shut it Down’ mural on Broadway in downtown Oakland. Photo: M.M. Ramírez, June 2020.

Markedly absent from media coverage of Oakland’s homicide rates or coverage on ‘crime waves’ across the US more broadly is a consideration of how the pandemic has left low-income people in an even greater state of economic precarity. The Alameda County Community Food Bank reports that food insecurity has increased by 50% in the county since the pandemic began, and unemployment rates remain at three times that of pre-pandemic levels. As Cat Brooks, co-founder of APTP, wrote:

If BIPOC people had stable incomes, secure housing, more opportunities to excel in life and a pathway to heal from the infectious disease of white supremacy, we would not see violence, we would see thriving communities and healthy people…. we can build the communities, the cities and the country we all want. But we have to invest in people on the front end instead of tombstones and jails on the back end.

Brooks clearly draws the connection between the gun violence taking place in Oakland and the lack of economic and social support people are facing in Oakland, East Oakland in particular, where the majority of shootings are taking place. Returning to Kelley, “capitalism does not operate from a purely color-blind market logic but through the ideology of white supremacy…a neoliberal variant of racial capitalism involves dismantling the welfare state; promoting capital flight; privatizing public schools, hospitals, housing, transit, and other public resources; and the massive growth of police and prisons” (2021: xv). The decimation of the welfare state, worker protections, and the array of public resources Kelley mentions across the US over the past 50 years has gone hand in hand with the rise of the prison-industrial complex (Gilmore 2007). This ‘neoliberal variant’, accelerated by the COVID-19 variant, has produced staggering rates of inequality that racial capitalism thrives upon.

These inequalities are deeply racialized and embedded in the US capitalist system, for as Cedric Robinson wrote: “racialism and its permutations persist, not rooted in a particular era, but in the civilization itself” (2021: 28). Racial capitalism manifests the tendency to “not homogenize but to differentiate – to exaggerate regional, subcultural and dialectical differences into racial ones” (2021: 26). These differentiations serve to reproduce economic inequality, often along racial lines, that manifest spatially in cities. Thus, the media discourses that frame Oakland as a violent place feed into carceral and white supremacist ideologies that justify said differentiations, ‘othering’ Black, Indigenous and Latinx residents in particular while reinforcing the idea that public safety requires police presence to keep ‘unruly’ populations under control. The neoliberal variant of racial capitalism thus produces “abandonment of the weakest members of society” (Gilmore 2007: 52); the police serve to uphold the racial capitalist order as residents experience severe social and economic deprivation.

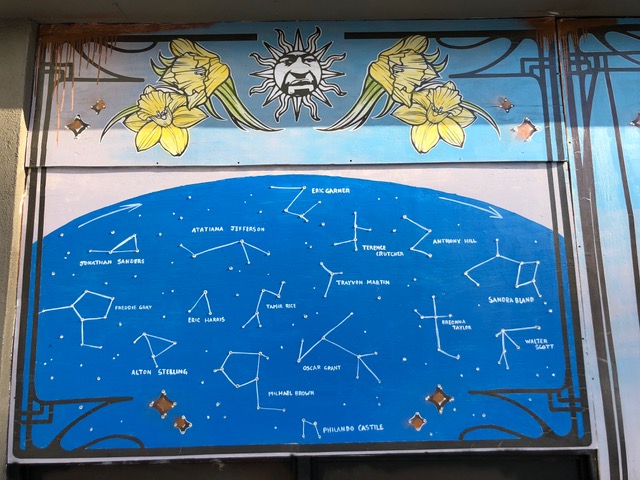

‘Constellations’ mural along 14th Street in Downtown Oakland. Photo: M.M. Ramírez, June 2020.

APTP’s caravan made its way from Lake Merritt to Lowell Park in West Oakland, where a few hundred participants were met with food, music, art, and chairs to rest upon under a large shady tree. After people dished up plates of food, the DJ turned down the music and Cat Brooks took the mic:

I don’t know if I’ve ever been as disturbed by OPD in the time I’ve been fighting OPD. We’re looking at the fact that our police department has turned into a political actor… They’re angry because we won $18 million to prevent crime, instead of ineffectively responding to it. They’re mad because we’re going to get to the gun before the bullet flies instead of standing with another mother before she puts her child in the ground… But in the face of their lies and fear-mongering and manipulation… we won $18 million reinvestment into our community… Our tax dollars that are going back to restore the resources and supports that were robbed from our community. And it’s not enough, but it’s more than we ever got… it’s going to provide us a platform… to prove that prevention, resources, economic opportunities, educational opportunities, mental health supports, housing, food, [and] arts keeps our community safe.

The ideological struggle over policing and public safety continues in cities like Oakland across North America. The carceral state holds tremendous power, and yet as Brooks stated, these $18 million are an entry point to build alternatives and demonstrate how meeting the basic needs of low-income people builds community safety. Organizers such as APTP continue building movements working towards abolition, where safety means care is central in society, as well as in the urban spaces we collectively build.

Postscript: On 7 December 2021, Oakland City Council voted to increase OPD’s operating budget by another $11 million by adding two additional police academies for 2021-23, effectively instating Mayor Schaaf’s proposed policing budget that City Council had voted against in June 2021

M.M. Ramírez (Twitter) is an urban scholar whose work explores the intersections of race, resistance, and urban space, and what the creative practices of people experiencing dispossession can tell us of the underlying racial, colonial, and capitalist structures of cities. She is an Assistant Professor of Geography at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, BC.

All essays on Racial Capitalism

Introduction: Racial Capitalism

Nik Theodore

The Stuff of Life: Frontier Infrastructures of Reproduction

Omar Jabary Salamanca

Racial Violence is Woven into the Fabric of our Cities

Libby Porter

The Cost of Platinum: Legacies of Violence and Subordination of Black Miners in South Africa’s Mining Towns

Asanda Benya

Policing, Racial Capitalism and the Ideological Struggle Over Public Safety

M.M. Ramírez

Blackness and Metropolitan Adjacency

AbdouMaliq Simone

Black Women on the Left of the Left in Brazilian Politics

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry & Edilza Sotero

Related IJURR articles on Racial Capitalism

Hamburg’s Spaces of Danger: Race, Violence and Memory in a Contemporary Global City

Key Macfarlane & Katharyne Mitchell

The Nomad, The Squatter and the State: Roma Racialization and Spatial Politics in Italy

Gaja Maestri

The Limits of Homeownership: Racial Capitalism, Black Wealth, and the Appreciation Gap in Atlanta

Scott N. Markley, Taylor J. Hafley, Coleman A. Allums, Steven R. Holloway & Hee Cheol Chung

Reappearance of the Public: Placemaking, Minoritization and Resistance in Detroit

Alesia Montgomery

Geographies of Algorithmic Violence: Redlining the Smart City

Sara Safransky

Sowing Seeds of Displacement: Gentrification and Food Justice in Oakland, CA

Alison Hope Alkon & Josh Cadji

‘Wilding’ in the West Village: Queer Space, Racism and Jane Jacobs Hagiography

Johan Andersson

‘Troubled Assets’: The Financial Emergency and Racialized Risk

Philip Ashton

Racialization and Rescaling: Post‐Katrina Rebuilding and the Louisiana Road Home Program

Kevin Fox Gotham

Race and the Production of Extreme Land Abandonment in the American Rust Belt

Jason Hackworth

Talkin’ ’bout the Ghetto: Popular Culture and Urban Imaginaries of Immobility

Rivke Jaffe

The Structural Origins of Territorial Stigma: Water and Racial Politics in Metropolitan Detroit, 1950s–2010s

Dana Kornberg

Controlling Mobility and Regulation in Urban Space: Muslim Pilgrims to Mecca in Colonial Bombay, 1880–1914

Nick Lombardo

Neoliberalism, Race and the Redefining of Urban Redevelopment

Christopher Mele

Reconfiguring Belonging in the Suburban US South: Diversity, ‘Merit’ and the Persistence of White Privilege

Caroline R. Nagel

Race Matters: The Materiality of Domopolitics in the Peripheries of Rome

Ana Ivasiuc

Fear and Loathing (of others): Race, Class and Contestation of Space in Washington, DC

Brandi Thompson Summers & Katheryn Howell

Everyday Roma Stigmatization: Racialized Urban Encounters, Collective Histories and Fragmented Habitus

Remus Creţan, Petr Kupka, Ryan Powell & Václav Walach

Disaster Colonialism: A Commentary on Disasters beyond Singular Events to Structural Violence

Danielle Zoe Rivera

The Aesthetics of Gentrification: Modern Art, Settler Colonialism, and Anti-Colonialism in Washington, DC

Johanna Bockman

Beyond the Enclave of Urban Theory

Austin Zeiderman